Probotics are a booming business, with sales in the billions of dollars each year and millions of customers in the US alone. Companies claim that the microbial concoctions can help consumers do anything from lose weight to sleep better, but researchers report inconsistent effects on people’s microbiomes.

Two studies published today (September 6) in Cell find individual differences in response to probiotic supplements—with some people resistant to any effects—and varied changes in gut microbes depending on the circumstances. The findings pave the way for the development of personalized probiotics and urge another look at the common practice of taking probiotics after antibiotics.

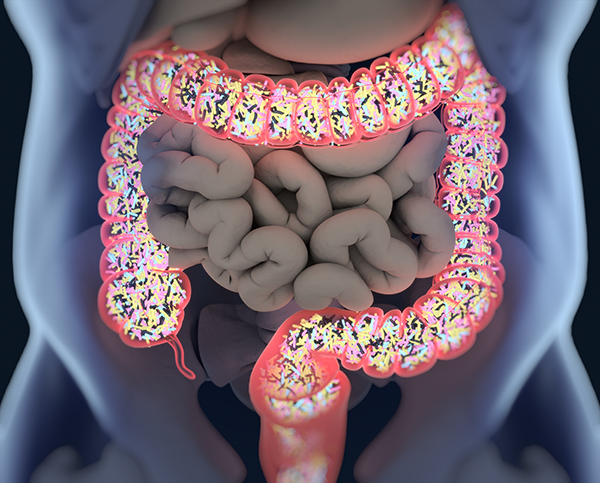

The experiments for both studies were led by Eran Elinav, an immunologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. The microbiome may be equally as important as the human genome for human health, he says. “But in contrast to the human genome, we speculate and hope and believe that we can intervene with the microbiome . . . by administration of probiotics.” Elinav and his team wanted to directly examine the effects of probiotics in mice and humans, in particular, on the gastrointestinal tract in its entirety, to see if probiotics actually colonize the gut.

According to Elinav, most of the studies that have looked into the effects of probiotics used stool samples as a proxy for what is happening in the gut. So to begin, he and his colleagues first contrasted the microbiomes in stool samples of mice and 25 healthy human volunteers to the microbial composition in either biopsies of mice’s gastrointestinal tracts or colonoscopy and endoscopy samples from the human subjects.

They found that the taxa and microbial gene expression in the stool only partially corresponded to those readouts sampled directly from the intestine.

“Solely relying on stool as a proxy for the microbiome is something we all do . . . that at least in some cases may lead to inaccurate conclusions,” says Elinav.

With that in mind, Elinav’s group used colonoscopy and endocscopy samples to explore the effects of probiotics on people’s gut microbiomes.

The authors divided 15 of the paid participants into two groups: 10 individuals received a preparation of 11 microbes that belong to four widely used probiotic families of bacteria and the other five received a placebo for a month. Three weeks into the treatment, the subjects received a second colonoscopy and endoscopy.

Elinav’s group found that six of the treated subjects had higher levels of colonization with the probiotic microbes, whereas the other four remained the same as their baseline. Furthermore, the researchers only found changes in microbial and human gene activity among those whose guts accepted the probiotics. This demonstrated that not everyone is receptive to probiotic consumption.

Just by looking at stool samples, the researchers could not differentiate between the two groups—the responders and the nonresponders—corroborating their earlier findings that stool samples may not always reflect what is happening inside the gut.

Neelendu Dey, a gastroenterologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington, notes that the studies are in a relatively small number of people, but “to be able to see these differences already is really exciting.”

Dey says it’s intriguing that people were either permissive or resistant to probiotics. “I suspect that with a larger cohort, we may actually see [these differences] as existing as more of a continuum,” he tells The Scientist…