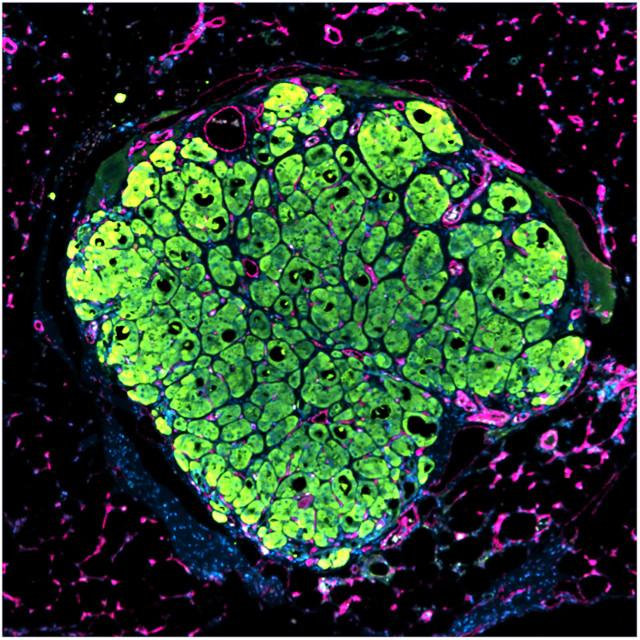

Patches of healthy tissue can contain groups of cells with genetic mutations, researchers reported June 6 in Science. In the study, they analyzed 29 different tissue types taken from 488 people. The results showed that the majority of the healthy individuals had clumps of mutated cells in at least one tissue sample taken. Most of the mutations are harmless, but some are linked with cancer, a finding that could reveal how cancer takes hold in healthy tissue.

“We now appreciate that we are mosaics, and that a substantial number of cells in our body already carry cancer mutations,” Iñigo Martincorena, a geneticist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the UK who was not involved in the study, tells Nature. “These are the seeds of cancer.”

Previous research had shown that different types of tissues accumulate genetic alterations with age. Skin cells pick up mutations when they are exposed to the sun, and others collect DNA errors during cell division. In previous studies, scientists had documented widespread mutations in skin, esophagus, and blood cells separately.

“But no one has really characterized this across many different tissues and across a great amount of individuals,” study coauthor Keren Yizhak, a postdoc at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University, tells NPR.

According to the team’s analysis, 40 percent of tissues had one large clump of mutated cells while about 5 percent had five or more clusters with mutations. “The skin, the lung and the esophagus were the ones where we found the highest amount of mutations,” Yizhak says. There’s high cell turnover in these tissues, and they are exposed to sunlight, in the case of skin, and other pollutants, in the case of lungs, so it follows that they’d have more genetic variation and some of that variation could lead to cancer.

“What we’re seeing are some of the earliest precancerous changes that are then going to accumulate more mutations,” Erin Pleasance, who studies cancer genomics at the British Columbia Cancer Agency in Vancouver, Canada, and who was not involved in the study, tells Nature. “Eventually a small proportion of these may become cancer.”

Jinghui Zhang, the chair of computational biology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, tells NPR that looking at the results with healthy skepticism is important because it’s not yet clear which mutations might contribute to the development of cancer.

Study coauthor Gad Getz, who runs the lab in which the work was done, agrees. “We need to distinguish between [cells] that eventually could become cancer and ones that maybe are on a dead end and will never become cancers,” he says. “And I don’t think we know yet what dictates what path the cells would take.”