At first, Stuart Harshbarger thought he’d injured his back lifting furniture and boxes. When the pain started, in 2008, “we’d just moved from Detroit to New York,” he explains. But the pain was excruciating, so the then 45-year-old international management consultant saw a doctor, who tested him for multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that often causes back pain. He got the results by phone while on a business trip in Germany, and was “scared to death,” he remembers.

In the decade since, Harshbarger’s odyssey has been typical of that of many multiple myeloma patients—though he’s made it past the median survival time for the disease, six years. He’s been through a series of standard treatments, most of which worked for some time until his cancer developed resistance, prompting his doctors to move him to another therapy. He was able to keep working for most of his time with the disease, but had to go out on disability beginning in mid-2016.

By 2017, “I was just completely out of options,” he recalls. At 55 years old, with a wife, one kid in high school and another in college, he was determined to hang on for as long as possible. “Every month that I can stay alive, I can improve and enhance the lives of my [family], who need my help right now,” he says. “So we’re just struggling for every month we can get, to keep the party going.”

That year, Harshbarger entered an immunotherapy trial of autologous CAR T cells engineered to target BCMA, a protein on the surface of multiple myeloma cells. The treatment didn’t seem to affect his cancer, and by this time, he was nearly bedridden. What Harshbarger didn’t yet know was that his doctors at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York had launched a small clinical trial—not of a new treatment per se, but of a different way of finding treatment options for patients like him.

The six doctors in the hospital’s multiple myeloma program see about 3,500 patients each year, says hematologist and oncologist Samir Parekh, many of them referred by other physicians after they stop responding to standard treatments. “The Sinai myeloma program seemed to have a lot of patients that were relapsing, that were either running out of options completely, or going on to clinical trials one after another without any clear biological rationale to guide them,” he says.

Parekh, who’s trained in genomics, wanted to see if those patients could benefit from a more tailored approach—one that looked beyond standard DNA tests that zoom in on specific loci in cancer cells’ genomes. Although such tests have been useful in identifying “actionable mutations”—those that indicate the cells could be vulnerable to a particular drug—in some solid tumors, Parekh says, they’ve been less effective in blood cancers such as multiple myeloma.

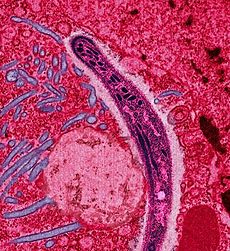

“The problem in myeloma is that patients . . . have drivers that are not entirely clear from just looking at pathology reports, and even DNA sequencing doesn’t always give us a clue as to how to manage these patients,” Parekh says. “So we had to expand our search beyond the conventional methods.” Performing RNA sequencing would give the researchers a peek not just at gene mutations, but at other changes in the cancer cells that might be treatment-relevant, such as copy number variations.

Parekh and colleagues chose 64 of the hospital’s patients—including Harshbarger—who had relapsed or were not responding to standard treatments, and sequenced their cancer cells’ DNA and messenger RNA. The team was looking for anything that would signal that these patients might respond to drugs that are approved for other cancers but not usually used against multiple myeloma….