One mouse is hunched over, graying, and barely moves at 7 months old. Others, at 11 months, have sleek black coats and run around. The videos and other results from a new study have inspired hope for treating children born with progeria, a rare, fatal, genetic disease that causes symptoms much like early aging. In mice with a progeria-causing mutation, a cousin of the celebrated genome editor known as CRISPR corrected the DNA mistake, preventing the heart damage typical of the disease, a research team reports today in Nature. Treated mice lived about 500 days, more than twice as long as untreated animals.

“The outcome is incredible,” says gene-therapy researcher Guangping Gao of the University of Massachusetts, who was not involved with the study.

Although the developers of the progeria therapy aim to improve it, they are also taking steps toward testing the current version in affected children, and some other scientists endorse a rush. The mouse results are “beyond anyone’s wildest expectations,” says Fyodor Urnov, a gene-editing researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. “The new data are an imperative to treat a child with progeria … and do so in the next 3 years.”

About 400 people in the world are estimated to have Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, which results from a single-base change in the gene for a protein called lamin A that helps support the membrane forming the nucleus in cells. The resulting abnormal protein, called progerin, disrupts the nuclear membrane and is toxic to cells in many tissues. Toddlers soon become bald and have stunted growth, body fat loss, stiff joints, wrinkled skin, osteoporosis, and atherosclerosis. People with progeria die on average around age 14 from a heart attack or stroke.

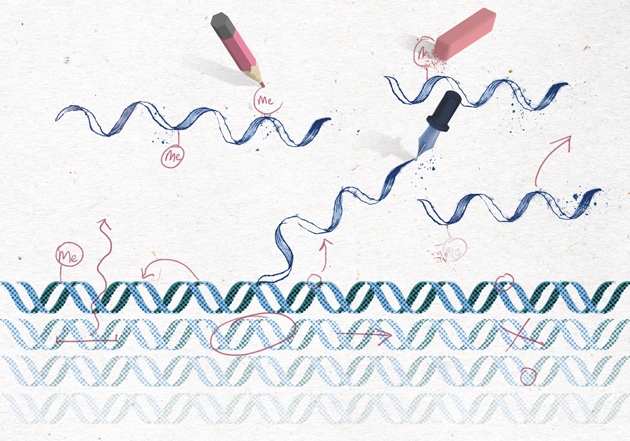

Researchers have previously used CRISPR to disrupt activity of the mutated gene for lamin A in progeria mice. But their health improved only modestly, and disabling a person’s good copy of the gene could cause harm. So David Liu of Harvard University and the Broad Institute turned to base editing, a DNA-changing method originally inspired by CRISPR and developed in his lab. Unlike CRISPR, which makes double-strand cuts in DNA, the base editor used in the progeria study nicks just one strand and swaps out a single base. Base editors have treated liver, eye, ear, blood, and brain disorders in mice, and Liu wanted to try one on an “infamous and devastating” disease that involves multiple organs or tissues.