Summary

The human microbiome constitutes a complex multikingdom community that symbiotically interacts with the host across multiple body sites. Host-microbiome interactions impact multiple physiological processes and a variety of multifactorial disease conditions. In the past decade, microbiome communities have been suggested to influence the development, progression, metastasis formation, and treatment response of multiple cancer types. While causal evidence of microbial impacts on cancer biology is only beginning to be unraveled, enhanced molecular understanding of such cancer-modulating interactions and impacts on cancer treatment are considered of major scientific importance and clinical relevance. In this review, we describe the molecular pathogenic mechanisms shared throughout microbial niches that contribute to the initiation and progression of cancer. We highlight advances, limitations, challenges, and prospects in understanding how the microbiome may causally impact cancer and its treatment responsiveness, and how microorganisms or their secreted bioactive metabolites may be potentially harnessed and targeted as precision cancer therapeutics.

Microbiome niches and cancer

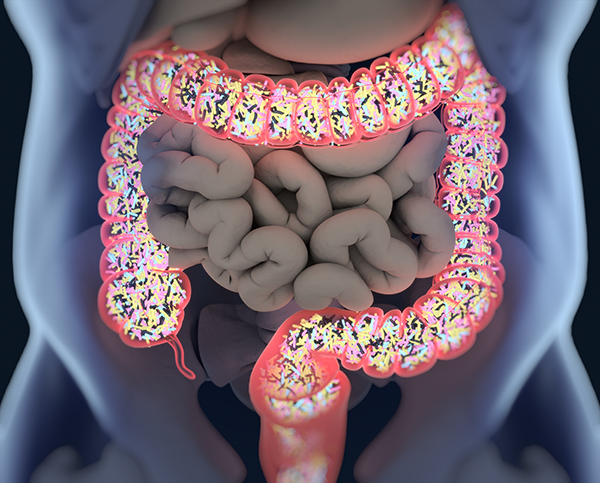

The human body harbors an estimated three trillion bacterial members that orchestrate a comprehensive interplay of physiological processes and disease susceptibilities (Sender et al., 2016). Although there is a similar number of bacterial cells as compared with human cells in the body, the 100-fold higher genetic diversity of bacteria encodes for outstanding mechanistic and metabolic competences that influence not only their own microbial niche, but host tissue–specific and immune cell functions (Gilbert et al., 2018). Beyond bacteria, the human microbiome is also composed of eukaryotic fungi and protozoa, and viruses (Ley et al., 2008). Overall, under healthy conditions, the host and its microbiome exist in symbiosis as a metaorganism by providing a nutrient-rich microenvironment in return for aid in digestion and metabolism (Schwabe and Jobin, 2013; Xavier et al., 2020). The gut, skin, and oral microbiomes are known to feature a highly enriched and diverse population of microbes; whereas, the vaginal microbiome is similarly well-studied but is rather characterized by lower diversity with highly specific and dominant microbial members (Cho and Blaser, 2012). Furthermore, organs and tissues, such as the lung, prostate, bladder, breast, liver, and pancreas that were previously considered to be sterile, are now, with the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS), identified as potentially harboring low-biomass microbial populations (Geller et al., 2017; Nejman et al., 2020; Parhi et al., 2020; Poore et al., 2020; Pushalkar et al., 2018). However, the exact nature of whether these microbiomes are natively established from commensal site-specific populations, or represent a transient migration from adjacent sites is still under debate.The general development and progression of cancer is considered to feature multiple distinguishable yet complementary and often overlapping hallmarks. By sustaining proliferation, evading cell growth suppression, activating invasion and metastatic pathways, enabling replicative immunity, inducing angiogenesis, and resisting autophagy, cancer cells effectively proliferate and evade the immune system (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000, Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). While these processes have been extensively studied for decades, potential microbiome impacts on cancer development, progression, and treatment responsiveness remained elusive until recently. In a disease scenario, each microbial niche (outlined in Figure 1) may influence cancer promotion via community-level interactions mediated by altered microbiome configurations (also termed “dysbiosis”) (Xuan et al., 2014) (Sobhani et al., 2011) (Farrell et al., 2012), direct interaction of individual members (Koshiol et al., 2016) (Pereira-Marques et al., 2019), or via secreted or modulated metabolites (Ma et al., 2018; Mager et al., 2020; Meisel et al., 2018). Niche-specific microbiome impacts on cancer (Helmink et al., 2019) can be exemplified by oral microbiome modulation of cancers in the oral cavity (oral squamous cell carcinomas [OSCC]), colon (colorectal cancer [CRC]) and pancreas (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [PDAC]). Likewise, the microbiomes of both male and female pelvic organs feature important implications for urological (Altmae et al., 2019) and gynecological (Laniewski et al., 2020) cancers, including prostate (Shrestha et al., 2018), cervical, endometrial, ovarian (Curty et al., 2019; Nene et al., 2019), and bladder (Bajic et al., 2019) cancers. In addition, the “intratumoral microbiome” may further contribute to local oncogenesis….