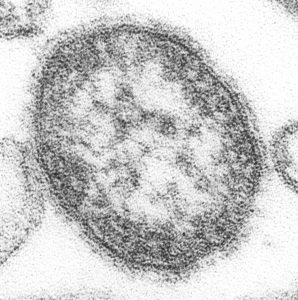

A “flesh-eating” version of group A Streptococcus bacteria, or necrotizing fasciitis, emerged because of just four mutations that occurred within 35 years in a single progenitor cell line, according to a paper published in PNAS. Researchers led by James Musser of the Houston Methodist Research Institute analyzed genome sequences of 3,615 strains of group A strep.

The flesh-eating strain of group A Streptococcus releases a protein that breaks down muscle, fat, and skin. Antibiotics can curb the infection, but the fatality rate can be as high as 70 percent for untreated cases.

Researchers traced the functions of four critical mutations that either helped the bacteria become much more infectious or create a more powerful version of the toxic protein. The first mutations happened sometime in the 1960s, the researchers found; the last likely occurred in or around 1983. Soon after, necrotizing fasciitis transformed into an epidemic disease.

“Nothing like this [study] has ever been done before,” David Morens, an epidemiologist at the National Institutes of Health, who did not participate in the study, told The Verge. “This is a pathogenic organism that evolved from something that wasn’t pathogenic, and then morphed into something extremely infectious—and now we know how it happened.”