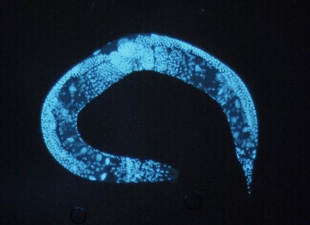

Researchers have devised a way to predict the lifespan of C. elegans, according to a study published in Nature. By outfitting the worms with proteins that fluoresce in response to free radicals in the mitochondria, then observing the number of “mitoflashes” in three-day-old worms, Meng-Qiu Dong of the National Institute of Biological Sciences in Beijing, China, and her colleagues could tell whether the animals would live longer or shorter than their average 21-day lifespan.

Fewer mitoflashes—indicating lower levels of free radicals, which result from cell metabolism and can damage DNA and proteins—were predictive of a longer lifespan; high mitoflash activity meant the worm was likely to die before 21 days.

“The finding that mitoflash frequency in early adulthood predicts lifespan corresponds well with our earlier observations that some early-life events and conditions could be good longevity predictors,” Leonid Gavrilov of the University of Chicago, who researches human aging , told New Scientist.

Dong’s team tested the technique on a C. elegans model with an extended lifespan of 39 days and found that, as expected, the longer-lived worms exhibited fewer mitoflashes at three-days old, with free radical levels peaking later in life. And worms harboring mutations that shortened lifespan showed the opposite pattern, with higher mitoflash frequency in three-day-old worms. Life-extending environmental stressors, such as starvation, heat shock, or pesticide exposure, also decreased day three mitoflash activity and delayed peak free radical levels.

“These results demonstrate that the day-3 mitoflash frequency is a powerful predictor of C. elegans lifespan across genetic, environmental, and stochastic factors,” the authors wrote.