In a seminal study published earlier this month in Nature, researchers used CRISPR gene-editing technology to repair a heart-disease inducing genetic mutation in human embryos. But not everyone in the scientific community bought their results.

This week, six scientists published a critique of the paper in the open-access preprint server bioRxiv. The team of skeptics, including Maria Jasin of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, took issue with one unexpected finding, namely, that the embryos used the healthy maternal DNA as a template to correct the defective sequence, rather than the DNA provided externally by the researchers.

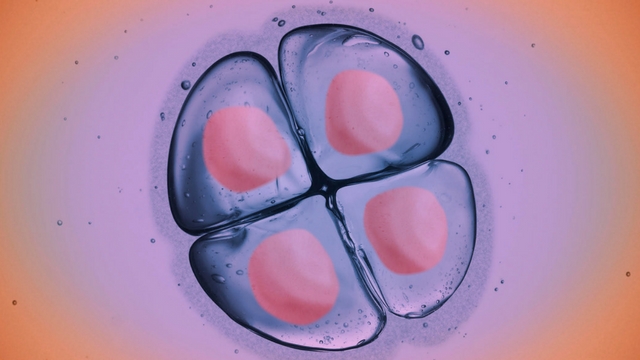

The authors of the Nature paper, led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov of Oregon Health & Science University, targeted a small genetic mutation in the MYBPC3 gene known to cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. They fertilized eggs from healthy donors with sperm from a man who harbors the defective gene and suffers from the condition. They wanted see if they could excise the snippet of diseased paternal DNA with CRISPR and replace it with a healthy sequence they had made in the lab.

According to Mitalipov’s team, the CRISPR’d embryos did something surprising: instead of taking up the mutation-free MYBPC3 DNA sequence, the embryos repaired the deletion using the homologous maternal sequence.

But the data presented by Mitalipov and his colleagues didn’t convince the group of skeptics, as “such a feat has not been observed in previous CRISPR experiments,” ScienceInsider reports.

In their dissenting paper, the critics assert that “the cell biology of fertilized eggs would appear to preclude the direct interaction between the maternal and paternal genomes” necessary for the homology directed repair mechanism that Mitalipov and colleagues describe.

“Clear evidence for a novel linkage of maternal and paternal alleles is an imperative,” which, the critics write, Mitalipov’s group did not provide. “Direct verification of gene correction,” including whether the maternal-for-paternal swap occurred, is possible, Jasin tells STAT.

As ScienceInsider reports, Jasin’s group outlines two alternative possibilities: the embryos developed without the paternal DNA in the first place, which has been known to happen, or the defective MYBPC3 gene was never actually replaced with the disease-free DNA.

Mitalipov and his colleagues “stand by [their] study’s key finding that human embryos are capable of effectively repairing disease-causing mutations by using a normal copy of the gene from a second parent as a template,” Mitalipov tells The Scientist in an email. He points out that the authors of the critique don’t offer any contradictory data, and says that his team intends to publish a response to each of the authors’ concerns.

“We recognize that these results must be confirmed by additional studies,” writes Mitalipov, and “encourage other scientists to reproduce our findings by conducting their own experiments on human embryos and publishing their results.”