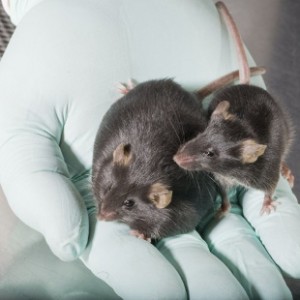

In mice whose sense of smell has been disabled, a squirt of stem cells into the nose can restore olfaction, researchers report today (May 30) in Stem Cell Reports. The introduced “globose basal cells,” which are precursors to smell-sensing neurons, engrafted in the nose, matured into nerve cells, and sent axons to the mice’s olfactory bulbs in the brain.

“We were a bit surprised to find that cells could engraft fairly robustly with a simple nose drop delivery,” senior author Bradley Goldstein of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine says in a press release. “To be potentially useful in humans, the main hurdle would be to identify a source of cells capable of engrafting, differentiating into olfactory neurons, and properly connecting to the olfactory bulbs of the brain. Further, one would need to define what clinical situations might be appropriate, rather than the animal model of acute olfactory injury.”

Goldstein and others have independently tried stem cell therapies to restore olfaction in animals previously, but he and his coauthors note in their study that it’s been difficult to determine whether the regained function came from the transplant or from endogenous repair stimulated by the experimental injury to induce a loss of olfaction. So his team developed a mouse whose resident globose basal cells only made nonfunctional neurons, and any restoration of smell would be attributed to the introduced cells.

See “Regularly Whiffing Essential Oils Can Retrain Sense of Smell”

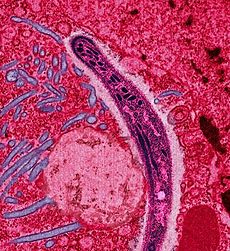

The team developed the stem cell transplant by engineering mice that produce easily traceable green fluorescent cells. The researchers then harvested glowing green globose basal cells (as identified by the presence of a receptor called c-kit) and delivered them into the noses of the genetically engineered, smell-impaired mice. Four weeks later, the team observed the green cells in the nasal epithelium, with axons working their way into the olfactory bulb.

Behaviorally, the mice appeared to have a functioning sense of smell after the stem cell treatment. Unlike untreated animals, they avoided an area of an enclosure that had a bad smell to normal mice.

To move this technology into humans suffering from a loss of olfaction, more experiments in animals are necessary, says James Schwob, an olfactory researcher at Tufts University who has collaborated with Goldstein but was not involved in the latest study, in an interview with Gizmodo. “The challenge is going to be trying to [engraft analogous cells] in humans in a way . . . that [would] not make things worse.”