A growing body of literature ties the gut microbiome to symptoms of depression in a seemingly circular relationship where each affects the other. However, many of the studies on this relationship merely link certain bacterial populations or diets to major depressive disorder—leaving open critical questions about the underlying mechanisms of how the gut microbes might influence depression.

Research published last month (May 3) in Cell Metabolism takes an important step toward filling such gaps, demonstrating in multiple animal species that there is likely a causative relationship between depression severity and serum levels of the nonessential amino acid proline, which the study finds depend on both diet and the activity of proline-metabolizing bacteria in the gut.

“To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time that a team actually demonstrates a causal relationship between proline intake and depressive behavior,” King’s College London metabolism researcher Sandrine Claus, who didn’t work on the study and is also chief scientific officer of the microbiome therapeutics company YSOPIA Bioscience, tells The Scientist over email. “I am unaware of a proline-mediated gut-brain axis. This is therefore a completely novel mechanism of action.”

Depression diet: the effects of proline

Previous research had found that proline, among other dietary compounds, seems to play a role in major depressive disorder, but “we found increased levels not only [in] major depression but also in subjects with moderate depression,” study coauthor José Manuel Fernández-Real, a researcher at the Girona Biomedical Research Institute and Dr. Josep Trueta Hospital, both located in Spain, explains. Indeed, the severity of the symptoms correlated with the subjects’ circulating proline.

Fernández-Real and his colleagues uncovered this when they compared people’s responses on an 80-item food intake questionnaire with scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a common clinical survey for diagnosing and measuring the severity of a person’s depression. Out of all the dietary nutrients in the questionnaire, Fernández-Real says, the one “most associated with depressive traits was precisely proline.” Blood tests in the same participants solidified the correlation between proline and depressive traits.

See “Gut Microbes May Play a Role in Mental Health Disorders”

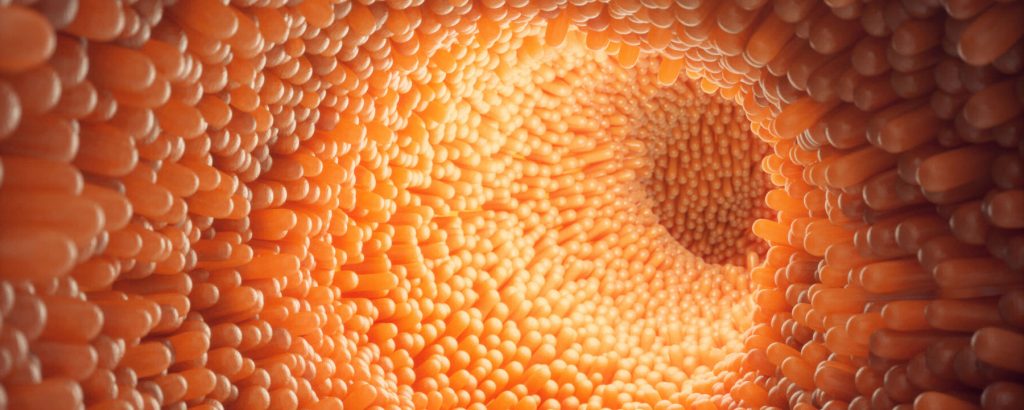

However, some discrepancies emerged within the data that demanded a closer look. “Not all subjects with increased proline in the diet had increased proline in the plasma,” hinting that some yet-undiscovered factor was involved, Fernández-Real explains. In search of that explanation, he and the other researchers determined the microbiome compositions of the human participants.

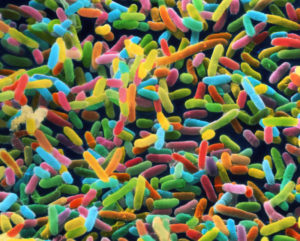

The paper notes that most previous studies attempting to do the same failed to achieve bacterial species-level resolution and have reached inconclusive and conflicting findings. But Fernández-Real and colleagues employed a multi-omics approach that allowed them to link microbial function to the specific biological pathways associated with depression, granting their study a level of resolution that Fernández-Real says was lacking from what he describes as underpowered previous studies.

In the study participants, plasma proline levels were associated with the presence and activity of specific gut bacteria—people with high proline consumption and higher plasma proline levels had different microbiome compositions than those who consumed the same amount of proline but had less circulating in their blood. Furthermore, the team found that the microbial communities of the former were associated with more severe depression.

How the gut microbiome influences depression

To determine whether there’s a direct link between proline and depression, the researchers revisited and modified mouse and Drosophila melanogaster models that they’d previously used to study how the microbiome influenced cognitive abilities….