Summary points

- Depression is the leading mental health—related cause of the global burden of disease and is the focus of World Health Day 2017.

- Despite robust evidence of the effectiveness of interventions ranging from self-care to clinical interventions, the vast majority of people with depressive symptoms do not receive any care.

- The majority of persons meeting the binary diagnostic criteria for depression have mild to moderate symptoms that most often do not need clinical interventions.

- A staged model, from wellness to distress to disorder, offers a hybrid between binary and dimensional approaches to classifying depressive symptoms, with specific interventions delivered through distinct delivery platforms addressing each stage.

- Such a staged approach is likely to be more efficient and acceptable to diverse audiences (from the general population to policy makers and practitioners) and provides the basis for these audiences to talk with one voice about this condition.

The past 12 months have been a momentous year for global mental health, the discipline of global health concerned with reducing the burden of mental ill-health and inequalities within and between nations. The World Bank and WHO jointly hosted the “Out of the Shadows” summit in Washington in April 2016 to highlight mental health as a global “development” priority, signifying a notable shift in emphasis from a narrower health focus to development more broadly. Twelve months later, the WHO celebrates its annual World Health Day in April 2017 on the theme of depression. This is a very timely (indeed, greatly overdue) recognition, for not only is depression the leading mental health—related cause of the global burden of disease but also because, despite the reams of evidence on how the suffering associated with this condition can be mitigated, vast proportions of people globally do not benefit from these interventions [1]. Even in the relatively better-resourced, middle-income countries such as India and China, up to 90% of patients with depression report not having sought or received any care for their symptoms [2].

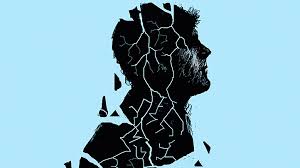

The slogan for World Health Day is “let’s talk,” emphasizing the central role of disclosure “as a vital component of recovery” by targeting the stigma surrounding mental illness, which acts as a barrier to people with depression seeking help. Significantly, the WHO campaign recommends that talking can involve a wide range of potential listeners, from family members and friends to health professionals, as well as encouraging open discussions about this condition in settings such as schools, the workplace, and in the media, “ultimately leading to more people seeking help.” I emphatically support the notion that seeking help must include both professional and nonprofessional actors. Despite this pragmatic recommendation, there is still little tangible action by governments and health systems to implement the evidence on effective interventions, and this is, at least in part, because of dissonant perspectives about the very nature of this condition. Indeed, some commentators view the discourse on the global burden of depression and the treatment gap as a culturally insensitive plot to export a failed psychiatric model to unsuspecting developing countries and a ploy to expand markets for pharmaceutical companies [3].

If we are to talk sensibly about depression, one must explicitly acknowledge that the term itself captures a very heterogeneous group of experiences, at least some of which can be addressed by “talking” with friends, while at other times, one may need a health professional. A major challenge to acknowledging this fundamental diversity of the experiences of depression is the current approach to the classification of the condition, which is, inadvertently, contributing to the large “treatment gaps” and the clash of ideas [4].