Two well-known gene mutations work in tandem to allow endometrial cells, the cells that line the uterus, to migrate outside of the organ, a phenomenon characteristic of diseases such as endometriosis and endometrial cancer, according to a study in mice and human tissue published August 7 in Nature Communications.

It’s been known for years that the two genes, ARID1A and PIK3CA, are associated with the diseases, but until now, it was unclear how. Endometriosis—a painful condition caused by endometrial tissue growing on organs outside of the uterus—and endometrial cancers are “intimately linked,” says Ronald Chandler, a reproductive biologist at Michigan State University and the senior author of the study. In both cases, endometrial cells migrate away from their usual position lining the uterine epithelium.

“Women with endometriosis are at higher risk for diseases such as endometrial cancer and ovarian cancer,” Chandler says. “But what we’ve found is that it’s this very specific cellular invasion process that’s really important for the spread of these abnormal endometrial cells.”

The results of the study have “huge consequences for identifying patients at even greater risk for advanced disease,” Amy Dwyer, a postdoc studying cancer biology at the University of Minnesota, tells The Scientist in an email.

ARID1A is mutated in 25–40 percent of patients with endometrial cancer and in more than 10 percent of endometriosis patients. It’s known to be a master regulator of gene expression and when it’s functioning normally, it’s considered a tumor suppressor. According to data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), 61 percent of patients who carry an ARID1A mutation also carry a PIK3CA mutation.

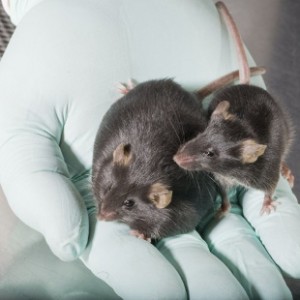

In order to gain a better understanding of how exactly these genes were influencing the development of endometrial cancer, Chandler and his team genetically engineered 49 mice to express different amounts of the genes.

“We basically recreated the same mutations that are found in humans in mice and then asked if those mutations are sufficient for causing cancer,” says Chandler.

The researchers examined the mice for signs of disease, including vaginal bleeding and tumors, and found only the mice that expressed both the ARID1A mutation and the PIK3CA mutation had these disease characteristics.

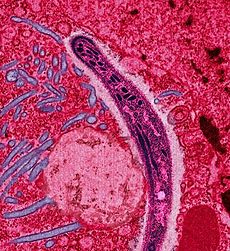

Next, the researchers used human tissue in vitro the explore how these mutations directly affected epithelial cells. They found that ARID1A mutation led to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a process in which epithelial cells revert to an earlier state when they are no longer tethered to their home in the uterus. This transition occurs in normal development, but in the wrong context, it can also lead to cancer. Still, it wasn’t enough to cause tumors to develop.

The trouble came when the PIK3CA mutation rescued some, but not all, of the epithelial cells, resulting in a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. The partial transition is what underlies the cells’ abilities to metastasize as epithelial sheets, which are known to be better than single cells at penetrating deep into tissue.

“Individually these two mutations have been associated with malignancy, but this paper is unique in helping identify the effects of concomitant mutations,” says Bradley Corr, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Colorado, in an email.

“They’re both affecting invasion and they’re doing so in slightly different ways. The end result is you have a transformation process that leads to cells being able to move as clusters elsewhere in the body,” which is characteristic of benign diseases such as endometriosis as well as malignant endometrial cancers, says Chandler.

Because the cellular invasion is involved in both types of disease, the researchers still don’t know why some patients with the mutations go on to develop cancer and others don’t. “If these mutations exist in different diseases,” says Chandler, “that tells us that the mutations alone do not cause the disease and it has to be something else.”

Konstantin Zakashansky, a gynecologic oncologist at Mount Sinai, says that “the value of this paper is really uncovering this intricate mechanism, and once it’s know how that drivers cancer, you can start to target those genes in hopes of reversing the process or preventing cancer in those at risk.