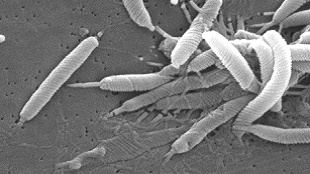

The ulcer-causing bacteria Helicobacter pyloriswiftly swarm to sites of microscopic damage on the surface of the mouse stomach. The microbes accumulate at these injury sites within minutes, and can slow tissue repair. These are the earliest events in H. pylori pathogenesis reported in vivo, according to a study published today (July 17) inPLOS Pathogens.

Previous studies have shown that both motility and chemotaxis are crucial to H. pylori colonization in the stomach. Mutants that are unable to sense pH gradients or concentrations of chemicals such as urea, arginine, or carbon dioxide are less capable of causing ulcers, requiring several times more bacteria than wild-type strains. But how these properties helped the bacteria colonize damaged stomach tissue was not clear.

The present study “is a very nice example of how very basic bacterial properties such as their abilities to swim or sense where they’re going—can have really important effects in disease,” said microbiologist Manuel Amieva of Stanford University who was not involved with the work. “We sometimes ignore these, because we look for disease-related factors.”

Alcohol, smoking, salt intake, and certain medicines can cause tiny traumas to the gastric epithelium. To test whether H. pylori could sense and respond to damage in this tissue microenvironment,Marshall Montrose of the University of Cincinnati and his colleagues induced ulcers in mice, and two days later, infected the animals with wild-type H. pylori. Ulcers in uninfected mice decreased to one-sixth of their initial size within nine days, and were indistinguishable after a month. Mice infected withH. pylori, however, still had visible ulcers at the end of that same time period. Significantly more bacteria were seen at the site of tissue damage than on an injured region within the same animal’s stomach.

Although earlier studies have examined factors affecting bacterial colonization of ulcers, “this paper really moves it to a different level,” said gastroenterologist Richard Peek of Vanderbilt University who was not involved in the work. “They’ve been able to show that if there’s pre-existing damage in the stomach—and it could be very, very minor—the bacteria hones in and will preferentially colonize that wounded area.”

Montrose and his colleagues then elucidated the role of motility and chemotaxis in the early steps of this process by damaging a miniscule region of the stomach epithelium in mice using lasers. Over the course of 15 minutes, they tracked the movements of wild-type bacteria, an immotile mutant that lacked flagellar motor proteins, and a mutant that was motile but incapable of chemotaxis.

Only wild-type bacteria gathered near the injury site, where they inhibited healing. Chemotaxis mutants, which could still remain near the epithelium, did not migrate to the lesion, although they did impair tissue repair. Immotile mutants, however, simply drifted away from the lining and into the gastric lumen. Montrose was impressed by how closely this minutes-long process mimicked the longer process of ulcer formation. “It really was a chance to bridge the experimentalist’s dream set-up and the pathophysiology you need to worry about and really need to work with,” he said.

But what the bacteria are swimming toward—or, perhaps, away from—is still a mystery. Although chemotaxis was not previously considered a crucial virulence mechanism, this work is “another example of how chemotaxis could be a target for therapy,” said Amieva. The bigger question, he added, is “why H. pylori causes an ulcer, whether it’s to gain better nutrients or a niche to survive.”

For now, the results suggest that even seemingly trivial insults to the stomach, such as a few drinks or popping an aspirin, could potentially attract H. pylori to sites where epithelial cells are sloughed off. These regions could provide an initiation point for H. pylori to find a foothold and cause disease. Factors such as alcohol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use were known to increase one’s risk of developing ulcers, but “this study is actually one of the first to identify a putative mechanism by which that risk is enhanced,” said Peek.

In future work, Montrose aims to address whether H. pylori also capitalizes on normal cell turnover— epithelial cells dying and being replaced—to find a niche to infect. “One cell is a small gap,” he said, “but for Helicobacter, that might be pretty attractive.”