Zika virus exposure in a mouse model can infect adult neural stem cells in the brain, leading to cell death and reduced proliferation.CELL STEM CELL, H. LI ET AL.Microcephaly and associated birth defects in babies born to mothers infected with the virus during pregnancy is considered the most serious consequence of the ongoing Zika outbreak. However, the increasing incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome and other neuropathologies linked to the mosquito-borne and sexually transmissible pathogen indicate that Zika virus infection represents a risk to adults, as well.

A number of recent studies have investigated how Zika virus infects fetal brain cells. Working in mice, scientists at Rockefeller University in New York City and their colleagues elsewhere have now examined how Zika virus infection impacts adult brain cells. As it turns out, as it has for fetal neural progenitor cells, Zika virus has tropism for adult proliferative neural progenitor cells and immature neurons. The team’s results were published today (August 18) in Cell Stem Cell.

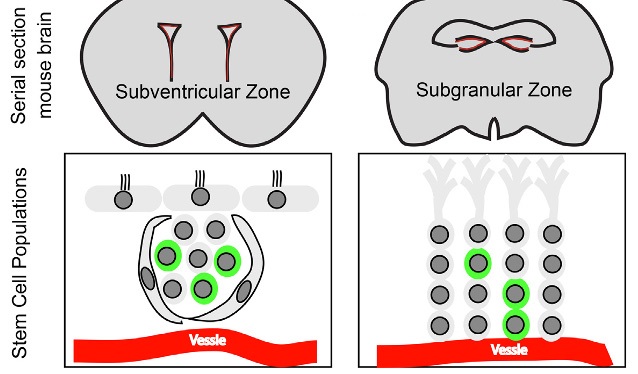

Zika virus infection can also induce apoptosis of adult neural progenitor cells in the anterior subventricular and subgranular zones of the mouse brain, the researchers reported.

The results of this mouse study show, “for the first time, that [Zika virus] can affect adult neurogenesis by increasing cell death in both adult neurogenic niches,” the anterior subventricular and subgranular zones,”Patricia Garcez, who studies neuoroplasticity at Brazil’s Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and was not involved in the work, wrote in an email to The Scientist. “Humans produce more than 700 neurons a day in adult hippocampus. . . . If the [neural] stem cells are depleted the effect would be long-lasting.”

While the findings “suggest that the virus has the potential to infect and destroy adult neural progenitor cells in . . . the adult mouse brain,” wrote Arnold Kriegstein, director of the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine’s developmental and stem cell biology program, they “do not shed light onhow the virus infects the adult cells.” This mechanism has yet to be uncovered.

The researchers worked with six-week-old mice triply deficient in interferon regulatory factor, which were infected by a single strain of Zika virus, and examined only once post-infection. “We limited our results to just this once strain of mice, this one strain of virus, and this one endpoint in order to have robust and quantitative results,” study coauthor Joseph Gleeson of Rockefeller University wrote in an email to The Scientist. “We used one of the strains of Zika that is known to cause human disease,” he added, “so the work is relevant to the current outbreak.”

As to whether the results in mice might translate to humans, Gleeson noted that “future research would require analysis of the stem cell populations as well as neurocognitive outcomes in adults following Zika infection.” Still, he wrote, it stands to reason that “some immunocompromised or even some healthy individuals might have reactions to Zika like we show in mice.”

Overall, said Kriegstein, who was not involved in the work, “this paper highlights the potential risk that Zika virus infection of adults might have unsuspected consequences—in at least some patients—that could affect brain function and behavior.”