Fat is a loaded tissue. Not only is it considered unsightly, the excess flab that plagues more than two-thirds of adults in America is associated with many well-documented health problems. In fact, obesity (defined as having a body mass index of 30 or more) is a comorbidity for almost every other type of disease. But, demonized as all body fat is, deep belly fat known as visceral adipose tissue (VAT) also has a good side: it’s a critical component of the body’s immune system.

VAT is home to many cells of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. These cells influence adipocyte biology and metabolism, and in turn, adipocytes regulate the functions of the immune cells and provide energy for their activities. Moreover, the adipocytes themselves produce antimicrobial peptides, proinflammatory cytokines, and adipokines that together act to combat infection, modify the function of immune cells, and maintain metabolic homeostasis.

Unfortunately, obesity disrupts both the endocrine and immune functions of VAT, thereby promoting inflammation and tissue damage that can lead to diabetes or inflammatory bowel disease. As researchers continue to piece together the complex connections between immunity, gut microbes, and adipose tissues, including the large deposit of fat in the abdomen known as the omentum, they hope not only to gain an understanding of how fat and immunity are linked, but to also develop fat-targeted therapeutics that can moderate the consequences of infectious and inflammatory diseases.

The omentum’s role in immunity

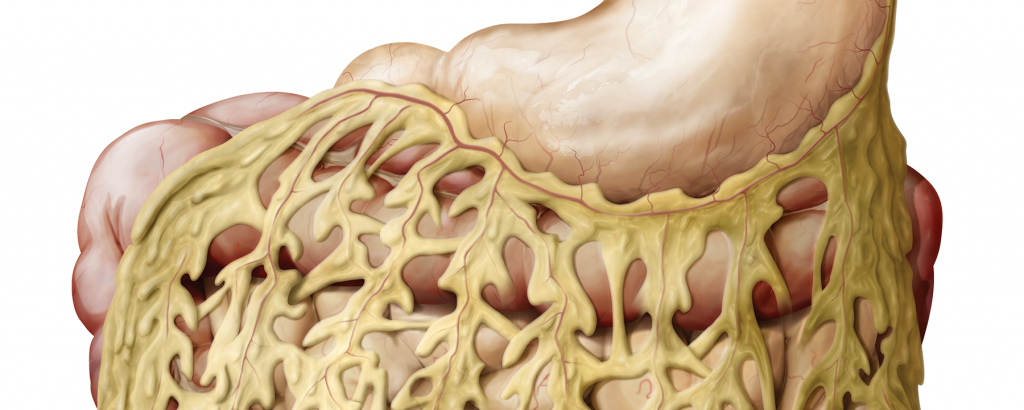

The omentum, a term derived from the Latin word for apron or cover, is a fold of fat that hangs below the stomach and covers the intestines. (See illustration on right.) Found in all people, even the most lean, the omentum is actually an independent organ. Hints about its functions (other than fat storage) exist in the early scientific literature. For example, after observing numerous cases in which the omentum adhered to ulcers of the gall bladder, stomach, and intestine; surrounded inflamed ovaries or ruptured appendices; and successfully plugged a hole in the diaphragm, a pioneering British surgeon at the turn of the 20th century referred to it as the “abdominal policeman.”

Consistent with this conclusion, we now know that the omentum supports the generation of blood vessels and fibrous connective tissue that can help repair damaged organs, and also promotes immune responses to fight infection. Many of the immune cells that reside within the omentum are found in aggregates termed fat-associated lymphoid clusters, or “milky spots” for their whitish appearance amidst the yellow fat. (See image on page 48.) In many ways, milky spots are analogous to lymph nodes—the small bean-shape organs that filter excess fluid from peripheral organs such as the skin, muscle, liver, and lungs. Milky spots, similarly, filter the fluid that flows from the abdominal cavity. The clusters of immune cells in both milky spots and lymph nodes sense microbes, damaged cells, and inflammatory mediators and initiate appropriate immune responses.

Despite their analogous functions, milky spots and lymph nodes have very distinct populations of leukocytes. For example, the antibody-producing B cells in milky spots and lymph nodes develop from different progenitors and have unique repertoires of antigen receptors. In particular, B cells in milky spots are associated with T cell–independent responses to bacterial and carbohydrate antigens, and often differentiate into IgA-producing cells that react with commensal bacteria in the intestine.2 Given that the omentum frequently adheres to ruptures in the intestine or appendix, it is likely that it helps defend against commensal organisms that might spill into the abdominal cavity after injury….