Neuroscientists have developed a method to pick out an individual solely by his connectome a pattern of synchronized neural activity across numerous brain regions. Researchers had observed previously that brain connectivity is a unique trait, but a new study, published today (October 12) in Nature Neuroscience, demonstrates that neural patterns retain an individual’s signature even during different mental activities.

“What’s unique here is they were able to show it’s not just the functional connectivity which is how different brain regions are communicating over time when you’re not doing a specific task but even how the brain is activated during a specific task that is also very fingerprint-like,” said Damien Fair, who uses neuroimaging to study psychopathologies at Oregon Health and Science University but wasn’t involved with the study.

Fair and others said individuated brain scans could be applied to better understand the diversity of mental illnesses often lumped into the same diagnosis. “We don’t kneed to keep going at the average. We have the power to look at individuals,” said Todd Braver of Washington University in St. Louis who did not participate in the study. “To me I find that really exciting.”

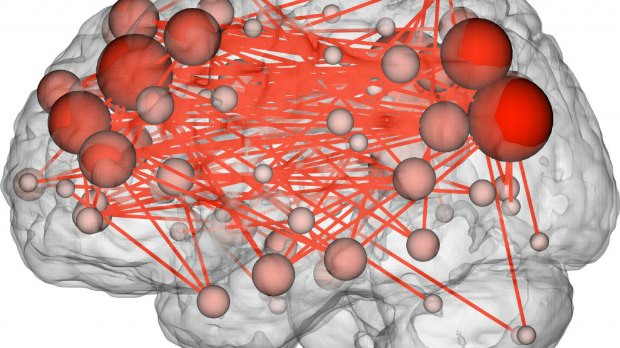

The research team, based at Yale School of Medicine, extracted data from the Human Connectome Project, which includes functional MRI (fMRI) data from about 1,200 people so far. The Yale team analyzed imaging data from 268 different brain regions in 126 participants. To create a connectome profile for each individual, the researchers measured how strongly the activity of a specific brain region compared to the activity of every other brain region, creating an activity correlation matrix.

Each person, it turned out, had a unique activity correlation matrix. The team then used this profile to predict the identity of an individual in fMRI scans from another session.

Depending on the type of fMRI scan assessed, the researchers could nail someone’s identity with up to 99 percent accuracy. Scans taken during mental tasks, rather than resting, made it more difficult, and the accuracy dropped to below 70 percent.

“Even though brain function is always changing, and we saw it’s slightly harder to identify people when they are doing different things, people always looked most similar to themselves” than to another participant, said Emily Finn, a graduate student in Todd Constable’s lab and the lead author of the study.

Fair pointed out that one of the most individualized brain regions is the frontoparietal cortex, which helps to filter incoming information. He has found the same result in his own work on fingerprinting connectivity. “It really seems important for making an individual who we are,” he said.

The ability to identify individuals even during tasks on different days would be important for clinical applications. Mental disorders are often classified by phenotype, or symptoms, that may represent a variety of underlying causes. “These types of technologies I think are going to help us personalize mental health better,” Fair told The Scientist. “We’ll have more information to say specifically what’s happening in your brain.”

Finn’s group was also able to associate a person’s connectome with his or her “fluid intelligence.” This trait is measured by asking people to solve a problem or find a pattern without using language or math skills or learned information. Finn told The Scientist that stronger connections between the prefrontal and parietal lobes, brain regions already known to be involved in higher order cognition, were most indicative of higher fluid intelligence scores. The results “suggest levels of integration of different brain systems are giving rise to superior cognitive ability,” she said.

“It’s not just this idiosyncratic fingerprint that they’re talking about that basically allows you to differentiate one individual from another,” Braver said of the study, “but it pushes the idea that [the connectivity signature is] functionally relevant, that those things may be related to things that we think are interesting individual differences, like intelligence.”

Finn cautioned that the intelligence correlation is more a proof of concept to link brain connectivity with behaviors, rather than something having real-life applications. “Hopefully, we could replace that with some variable, like a neuropsychiatric illness or [predicting] who’s going to respond best to some treatment.”