Preliminary research suggests that using CRISPR to treat cancer is safe in humans and could become a feasible therapeutic method in the future, although its efficacy is still unknown. Results from an ongoing clinical trial, led by hematologist Edward Stadtmauer of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, will be presented at the American Society of Hematology meeting in December. The presentation abstract was published online yesterday (November 5).

See “CRISPR Inches Toward the Clinic”

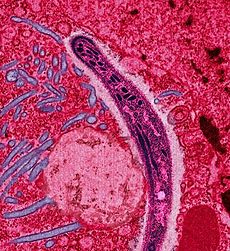

Stadtmauer’s team procured T cells from three cancer patients—two with multiple myeloma and one with sarcoma—through a blood draw, and genetically modified the cells’ DNA using CRISPR. They inserted a gene from a virus into the immune cells that causes the cells to target the protein NY-ESO-1, found on cancer cells, and deactivated three genes within the cells that could interfere with their cancer-fighting ability. Two of the gene edits inactivate TCRα and TCRβ, causing T cell receptors to be removed. Without the receptors, the the cells can more easily bind to cancer cells. The third edit disables PDCD1, a gene that can kill T cells.

The researchers then infused the cells back into the patients, who have since had no significant adverse effects after six months, according to NPR. Research is still underway to determine whether the altered T cells are having any effect on the cancers, according to the The New York Times.

“This trial is primarily concerned with three questions: can we edit T cells in this specific way? Are the resulting T cells functional? And are these cells safe to infuse into a patient? This early data suggests that the answer to all three questions may be yes,” says Stadtmauer in a news release. The team is planning to conduct a clinical trial with 18 patients in the future.

“I’m just so excited about this,” Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley, who help develop CRISPR techniques and was not involved in the study, tells NPR. “It’s an important step on the path toward using CRISPR-Cas genome editing in patients and shows the potential of this technology to be a safe and effective therapy.”