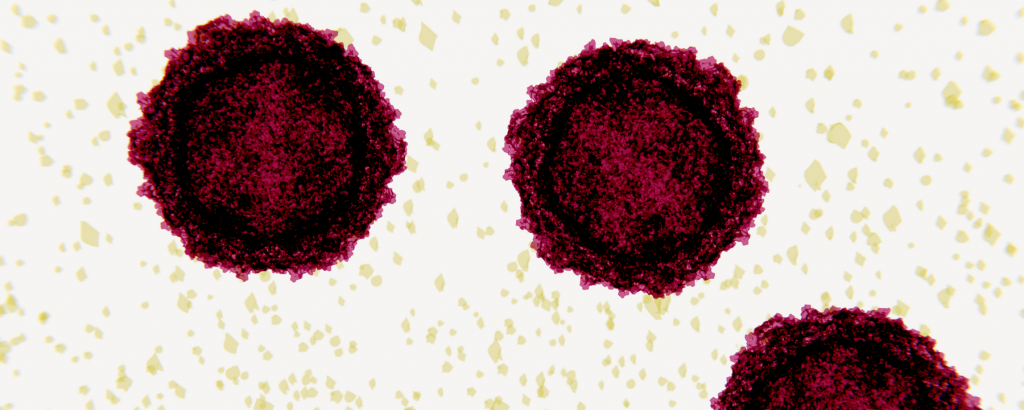

A mysterious, polio-like condition that leads to paralysis in children likely involves an enterovirus, according to research published last week (June 10) as a preprint in bioRxiv. Researchers linked acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), a rare disease that’s been on the rise in the US since 2014, to a virus called EV-D68 and related pathogens, although it’s not clear whether this group of viruses is the sole cause.

“It is a very good paper,” Stephen Elledge, a Harvard Medical School geneticist who was not involved in the work but helped develop the method off which it was based, tells STAT. The study “demonstrates clearly and convincingly what others had some data for that were not conclusive, that AFM is likely to be caused by enteroviruses.”

AFM has been diagnosed in more than 500 children in the last five years. The pattern of cases is similar to that typical of enterovirus infections—that is, alternating between high and low incidence from one year to the next. According to STAT, there were 22 cases in 2015, 149 in 2016, 35 in 2017, and 232 in 2018.

See “More Reports of Children Being Paralyzed by Mysterious Disease”

The disease attacks gray matter in the spinal cord, so neurologist Michael Wilson of the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) wanted to investigate whether an enterovirus might be present in that part of the body in affected children.

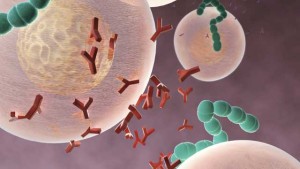

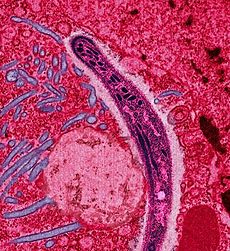

To identify evidence of any past viral infections in AFM patients, the researchers adapted a method developed by Elledge that uses bacteriophages to collect antibodies present in a sample, in this case, the patients’ spinal fluid.

The test identified signs of infection by EV-D68 as well as other enteroviruses in a group of more than 40 children with AFM. “Finding evidence of antibodies in spinal fluid in response to the virus is an important first step toward a diagnostic test for AFM and a path toward treatment,” the CDC says in a statement to STAT.

“While continued vigilance for other possible etiologies of AFM is warranted, together, our combined [results support] the notion that EV infection likely underlies the majority of AFM cases tested in this study,” the authors write in their paper, which has yet to undergo peer review. “These results offer a roadmap for rapid development of enteroviral cerebrospinal fluid antibody assays to enable efficient clinical diagnosis of enterovirus-associated AFM in the future.”