Scientists in Korea have injected human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived retinal support cells into the eyes of four men with macular degeneration, according to a study published today (April 30) inStem Cell Reports. Three of the men experienced vision improvements in their treated eyes in the year following the procedure, while the fourth man’s vision remained largely the same. The trial adds to growing evidence that injecting hESC-derived cells is feasible, feeding hopes for their future therapeutic use.

This latest study follows on two papers published inThe Lancet in 2012 and 2014, which similarly demonstrated that hESC-derived cells could be safely injected into the space behind the retina in macular degeneration patients. These studies, sponsored by the Massachusetts-based company Advanced Cell Technology (now Ocata Therapeutics), were the first published accounts describing the application of hESC-based therapies in humans.

Korean company CHA Biotech carried out the new trial. Ocata provided the hESCs and some methodological instruction. “Together with the results here in the US, I think this bodes well for the future of stem cell therapies,” said study coauthor Robert Lanza, chief scientific officer at Ocata.

Jeanne Loring, a stem cell researcher at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, agreed that the apparent safety of the therapy in the subjects tested is encouraging. However, she added, it would be difficult to draw firm conclusions about efficacy based on such a small study. “I think it’s still anecdotal that some people seem to improve,” said Loring.

“At least it shows safety,” said Magdalene Seiler, a project scientist at the University of California, Irvine. “Whether it works in the long term is up for debate.”

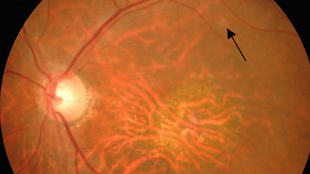

Like many other teams working to develop stem cell-based therapies, the Ocata-led team sought to treat a disease of the eyes in part because the organs are accessible. For the current study, the researchers treated two men with dry age-related macular degeneration, aged 65 and 79, as well as a 40-year-old man and a 45-year-old man, both with Stargardt macular dystrophy, an earlier-onset inherited disease. Both forms of macular degeneration lead to vision loss resulting from the destruction of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells. RPE cells support retinal photoreceptor cells by nourishing them and cleaning up their waste. Without functional RPEs, retinal photoreceptors die.

The researchers differentiated hESCs into RPE cells and injected them into one eye of each patient, hoping that the transplanted RPE cells would take root and replace those that had been lost, preventing further loss of photoreceptors. Lanza explained that “the goal of the therapy was not to improve vision.”

Even so, the vision of three of the men improved by two to four lines of letters on a standard vision test. The vision of the fourth patient, the older man with age-related macular dystrophy, improved by just one letter —a negligible change.

Because of the study size, it is too early to conclude whether the treatment systematically improves vision in patients, said Lanza. However, he hypothesized that patients could have experienced vision improvements because the infusion of new RPE cells revived photoreceptors that had gone dormant but were not yet dead.

Lanza was also encouraged to see that the transplanted cells did not form tumors or differentiate into cells other than RPEs, a major concern among researchers in the field. Regulators “don’t really want to see a tooth in the eye or they don’t want to see beating heart cells in the wrong place,” Lanza said. By carefully screening all cells transplanted into patients, researchers were able to avoid transplanting cells that were not fully differentiated and could, therefore, have formed unwanted tissues.

The scientists were also relieved to see that the patients’ immune systems did not reject the transplanted cells. Like the brain, the eye is immune privileged, meaning that it is largely inaccessible to immune cells. To be safe, the researchers still gave the patients immunosuppressive drugs for a limited period before and following the surgery. It is unclear whether this was necessary.

Finally, by focusing on men of Asian descent, the study added to the diversity of the small group of patients who have received transplanted hESC-derived cells. The previous Lancet studies largely focused on Caucasian patients. Asian and Caucasian patients have different alleles that contribute to risk for age-related macular degeneration.

CHA Biotech is hopeful to get the go-ahead from Korean regulators to proceed with Phase 2 trials using hESC-derived cells to treat Stargardt macular dystrophy this year.

Ocata, meanwhile, will start Phase 2 trials for both Stargardt macular dystrophy and age-related macular degeneration in the “next several months,” according to Lanza. Meanwhile, researchers at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Japan last year began a trial to test induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived RPE cells for the treatment of macular degeneration.

The new work adds to the climate of hope for stem cell therapies. “It’s inspiring other scientists,” said Loring, whose team is working to eventually treat people with Parkinson’s disease with iPSC-based therapies. “It makes us feel like we’ll be able to do similar things in whatever diseases we’re studying.”