Concerns about coronavirus variants that might be partially resistant to antibody defences have spurred renewed interest in other immune responses that protect against viruses. In particular, scientists are hopeful that T cells — a group of immune cells that can target and destroy virus-infected cells — could provide some immunity to COVID-19, even if antibodies become less effective at fighting the disease.

Researchers are now picking apart the available data, looking for signs that T cells could help to maintain lasting immunity.

“We know the antibodies are likely less effective, but maybe the T cells can save us,” says Daina Graybosch, a biotechnology analyst at investment bank SVB Leerink in New York City. “It makes sense biologically. We don’t have the data, but we can hope.”

Coronavirus vaccine development has largely focused on antibodies, and for good reason, says immunologist Alessandro Sette at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California. Antibodies — particularly those that bind to crucial viral proteins and block infection — can hold the key to ‘sterilizing immunity’, which not only reduces the severity of an illness, but prevents infection altogether.

That level of protection is considered the gold standard, but typically it requires large numbers of antibodies, says Sette. “That is great if that can be achieved, but it’s not necessarily always the case,” he says.

Killer cells

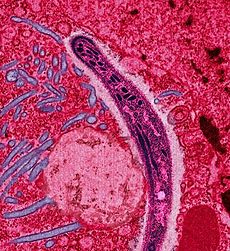

Alongside antibodies, the immune system produces a battalion of T cells that can target viruses. Some of these, known as killer T cells (or CD8+ T cells), seek out and destroy cells that are infected with the virus. Others, called helper T cells (or CD4+ T cells) are important for various immune functions, including stimulating the production of antibodies and killer T cells.

T cells do not prevent infection, because they kick into action only after a virus has infiltrated the body. But they are important for clearing an infection that has already started. In the case of COVID-19, killer T cells could mean the difference between a mild infection and a severe one that requires hospital treatment, says Annika Karlsson, an immunologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. “If they are able to kill the virus-infected cells before they spread from the upper respiratory tract, it will influence how sick you feel,” she says. They could also reduce transmission by restricting the amount of virus circulating in an infected person, meaning that the person sheds fewer virus particles into the community.

T cells could also be more resistant than antibodies to threats posed by emerging variants. Studies by Sette and his colleagues have shown that people who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 typically generate T cells that target at least 15–20 different fragments of coronavirus proteins1. But which protein snippets are used as targets can vary widely from person to person, meaning that a population will generate a large variety of T cells that could snare a virus. “That makes it very hard for the virus to mutate to escape cell recognition,” says Sette, “unlike the situation for antibodies.”

So when laboratory tests showed that the 501Y.V2 variant identified in South Africa (also called B.1.351) is partially resistant to antibodies raised against previous coronavirus variants, researchers wondered whether T cells could be less vulnerable to its mutations.

Early results suggest that this might be the case. In a preprint published on 9 February, researchers found that most T-cell responses to coronavirus vaccination or previous infection do not target regions that were mutated in two recently discovered variants, including 501Y.V22. Sette says that his group also has preliminary evidence that the vast majority of T-cell responses are unlikely to be affected by the mutations.

If T cells remain active against the 501Y.V2 variant, they might protect against severe disease, says immunologist John Wherry at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. But it is hard to know from the data available thus far, he cautions. “We’re trying to infer a lot of scientific and mechanistic information from data that doesn’t really have it to give,” he says. “We’re kind of putting things together and building a bridge across these big gaps.”….