The evidence continues to mount over the importance of the human microbiome—especially within the intestinal tract—for supporting optimal growth and overall health and wellness. Over the past several years scientists have described scenarios wherein the microbiome has either directly affected or strongly associated with diseases ranging from obesity and diabetes to heart disease and some forms of cancer. An area of microbiome research that is beginning to get more attention is how these communities of microbes impact infant development.

A team of researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) in St. Louis believes they have found a key component of human breast milk that promotes healthy infant growth and how interactions with the gut microbiota drive this process.

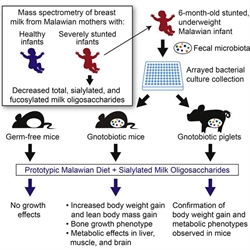

Childhood malnutrition causes over 3 million deaths every year and leads to stunted growth, as well as deficits in immune and cognitive development. The WUSM researchers partnered with colleagues in Malawi, Africa, where almost half of all children under five show stunted growth. The scientists were able to obtain small samples of human breast milk from the mothers of healthy or stunted babies.

Through the analysis of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), the investigators found that HMOs containing sialic acid residues, which have been implicated in proper brain development, were far more abundant in the breast milk of mothers with healthy versus stunted babies, suggesting that these breast milk sugars may promote healthy infant growth. To determine if their hypothesis was correct the researchers established animal models that allowed both diet and the gut microbiome to be manipulated, as a concurrent study from the same research team found that gut microbes are important mediators of normal growth.

“To explore this association, we colonized young germ-free mice with a consortium of bacterial strains cultured from the fecal microbiota of a 6-month-old stunted Malawian infant and fed recipient animals a prototypic Malawian diet with or without purified sialylated bovine milk oligosaccharides (S-BMO),” the authors wrote.

The scientists introduced a collection of bacterial strains isolated from the fecal sample of an undernourished infant into mice or piglets. Subsequently, the team fed the animals a prototypical Malawian diet consisting of corn, legumes, vegetables, and fruit, which on its own is insufficient for healthy growth.

The findings from this study were published recently in Cell through an article entitled “Sialylated Milk Oligosaccharides Promote Microbiota-Dependent Growth in Models of Infant Undernutrition.”

Additionally, the researchers wrote that “S-BMO produced a microbiota-dependent augmentation of lean body mass gain, changed bone morphology, and altered liver, muscle, and brain metabolism in ways indicative of a greater ability to utilize nutrients for anabolism.”

This study helps to identify some of the essential components of breast milk that are needed for infant health and how they interact with the gut microbiome and other dietary components.

“This capacity to look in a very controlled way at how food is partitioned among members of a microbial community and how the metabolic output of that community can affect human biology is part of our ongoing agenda,” explained senior study author Jeff Gordon, M.D., professor and director of the Center for Genome Sciences and Systems Biology at Washington University in St. Louis.

The researchers were excited by their findings and hopeful for the future, but careful to point out that more needs to be learned about how different types of bacteria interact with components of breast milk and complementary foods, and to ensure that harmful gut bacteria would not thrive on those components and thereby gain an advantage over beneficial microbes.

“Even though our intentions are good, we want to make sure we do no harm,” Dr. Gordon noted. “This is just the beginning of a long journey, an effort to understand how healthy growth is related to the normal development of the gut microbiota, and how we can establish whether durable repair of microbiota immaturity may provide better clinical outcomes.”