Myc, a transcriptional regulator that is overexpressed in several human cancers, appears to have a direct role in preventing immune cells from efficiently attacking tumor cells. The oncogene in part sustains tumor growth by increasing the levels of two immune checkpoint proteins, CD47 and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), which help thwart the host immune response, according to a study published today (March 10) in Science.

“It’s been shown that MYC is deeply involved in tailoring the external environment of proliferating tumor cells,” said Gerard Evan, a cancer researcher at the University of Cambridge, U.K., who was not involved in the study. “What is interesting here [is that MYC] tailors the ability of T cells to come in and survey the expanding tissue.”

“This study suggests . . . that MYC can drive expression of immune evasion molecules in cancer cells,” wrote Thomas Gajewski, a cancer researcher at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the study. “This is a novel result that could have translational implications if Myc-targeted drugs are found to be effective in the clinic.”

MYC is required at low levels for cell growth and proliferation. Its continued overexpression, however, is associated with tumor growth in mouse models of cancer. Dean Felsher of the Stanford School of Medicine and his colleagues had previously shown that when oncogenes like Myc are inactivated in certain mouse tumors, the tumors could only be fully cleared when the immune system—including activation and recruitment of CD4+ T cells—was switched “on.”

“We initially observed that tumors don’t regress as well in immune-compromised mice, even when we turn MYC off,” Felsher told The Scientist.

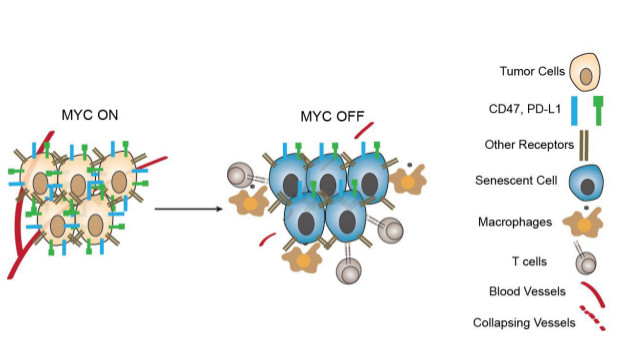

For the present study, Felsher’s team sought to identify how Myc inactivation is related to an antitumor immune response. In transgenic mouse models of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and liver cancer (both inducible by overexpression of MYC), the researchers found that levels of PD-L1 and CD47 correlated with MYC activation.

PD-L1 is part of a signaling pathway that normally helps cease T cell activation following an immune response. CD47 is also a cell surface protein; it functions to inhibit macrophages and other immune cells from engulfing cells on which it resides.

When the researchers turned off MYC overexpression, they observed decreased levels of CD47 and PD-L1. Preventing expression of MYC in human T-ALL cell lines and in three human solid tumor cell lines also decreased the levels of the two proteins, but

did not affect the expression of several other immune cell surface receptors. CD47 and PD-L1 expression also correlated with Myc expression in three primary, human tumor samples, the researchers showed. “So far, we know that CD47 and PD-L1 are causally involved,” said Felsher. “It is likely that other immune checkpoint molecules are also involved and we are now looking into that more extensively.”

The researchers then demonstrated that decreasing the expression of CD47 and PD-L1 is likely to be necessary for tumor regression. They found that if Myc is inhibited but CD47 and PD-L1 are continually overexpressed, tumors in mice with MYC-driven T-ALL cells persisted. This confirmed the role of these Myctargets in regulating immune system evasion, said Gajewski. While inhibiting Myc overexpression normally prevents angiogenesis, continued expression of the two immune proteins despite Myc inhibition allowed angiogenesis to continue.

MYC directly bound to the promoters of these two immune genes in both mouse and human transformed cells, the researchers showed. Using a human bone cancer cell line, the team found that MYC bound the promoters of the two genes only when present at the high levels found in cancer cells.

To Felsher’s mind, the findings validate Myc as a promising anticancer target.

“The current study is a pioneering advance in our understanding of how Myc affects not only the tumor cell, but also the surrounding tissue,” Douglas Green, an immunologist and cancer researcher at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital in Tennessee who was not involved in the work, wrote in an email to The Scientist. “It will important to follow up the importance of PD-L1 and CD47 in tumor types that are not driven by MYC overexpression. This would significantly extend the implications of the findings.”

“What happens in cancer is not invented de novo by oncogenes, but rather represents hijacked versions of normal processes,” said Evan.

“From this work, we presume that in normal proliferating cells, MYC regulates PD-L1 to exclude T cells after proliferation stops, T cells come back into the tissue,” he continued. “Now, the question is, why on Earth are T cells not wanted during proliferation? . . . That is the most intriguing aspect of this study.”