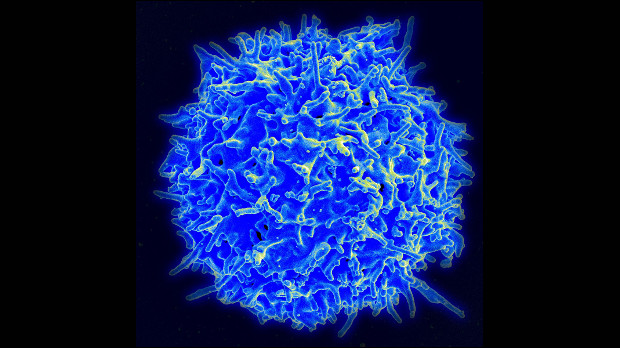

Each newly-formed T cell bears a unique T cell receptor (TCR) that recognizes a particular antigen. But how a given TCR shapes the fate of its cell and that cell’s progeny was largely unknown. Today (August 26), scientists at MIT report in Science Immunology on their discovery that precursor T cells with precisely the same TCR don’t necessarily follow the same developmental path.

“The main take-home message is that T cells with identical specificity . . . can really differentiate into very distinct subtypes of T cell depending on the environment in which they are located,” said mucosal immunologist Daniel Mucida of Rockefeller University in New York who was not involved in the study.

During T cell development, the genes encoding the TCR are shuffled and recombined by special genetic mechanisms to create an individual version of the receptor protein expressed on the cell’s surface. A variety of T cell types exist: some, like helper and cytotoxic T cells, promote strong immune responses against foreign invaders, while others. like T regulatory cells (T regs), suppress excessive inflammation. It has been observed that the repertoire of TCRs found on one subtype—for example, T regs—tends not to overlap with that found on others. This finding could indicate that the type of antigen recognized by a particular TCR can influence the type of T cell that subsequently develops.

To investigate this possibility, postdoctoral researcher Angelina Bilate of MIT’s Whitehead Institute and colleagues took the nucleus from a mature intestinal mouse T reg cell—in which the TCR genes were already rearranged—and used it to create cloned animals in which every T cell expressed that very same TCR (the mice were genetically incapable of further TCR gene rearrangements).

Thinking it likely that these transnuclear mice would only contain T regs, Bilate was “completely surprised” to find that while the animals did produce a small amount of T regs, they also contained an entirely different type of T cell called intraepithelial lymphocytes (iELs). “It was like a bucket of cold water on me,” she told The Scientist.

In contrast to T regs’ anti-inflammatory nature, iELs can adopt both a cytotoxic phenotype—expressing the proinflammatory cytokine interferon gamma—or an antiflammatory state. T regs and iELs share few similarities, said Mucida. “It’s not like a subtle difference in the type of function they can perform. They are very distinct.”

Bilate and colleagues found that the two cell types also differed in their locations within the intestine. The T regs primarily resided in the mesenteric lymph nodes and lamina propria—the layer of connective tissue at the base of the mucus membrane—while iELs dominated the epithelial layer.

However, because the cells shared the same TCR, they presumably recognized the same antigen. Although the identity of that antigen is not yet known, the team showed that it is microbial: in antibiotic-treated mice, the T cells did not develop into either T regs or iELs. Instead they remained “naive”—the status of T cells prior to activation by TCR-antigen interaction.

“The obvious next question is: How do the signals from the microbiota get differentially transmitted to divert the cells in one direction or the other?” said immunologist Dan Littman of New York University. “Is it different antigen presenting cells or some other property of the microenvironment where [the cells] are situated?”

In the mammalian gut, immune cells must perform a delicate balancing act of preventing pathogenic invaders while tolerating dietary antigens and commensal microbes. Occasionally this balance is tipped, such as in food allergies or other inflammatory bowel conditions. But, if you “understand the factors that are involved in the modulation of these cells,” said Mucida, then maybe “you can figure out what is required to correct unbalances that occur under pathological conditions.”