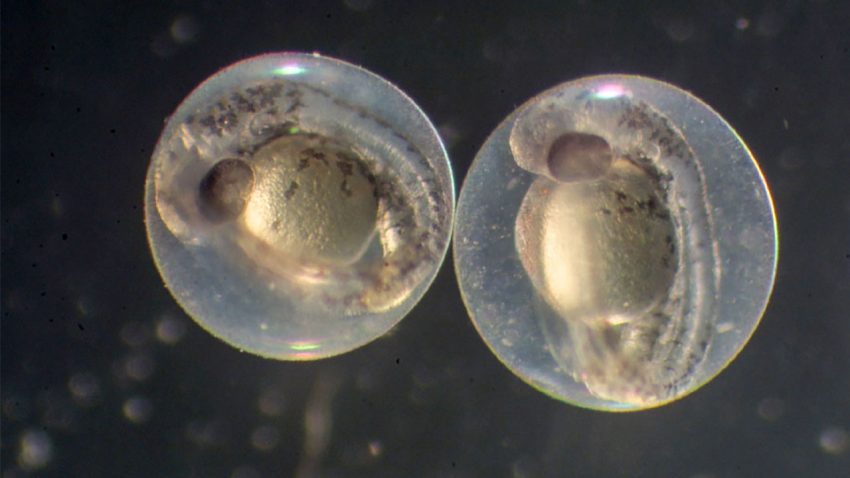

Russian biologist Denis Rebrikov has started gene editing in eggs donated by women who can hear to learn how to allow some deaf couples to give birth to children without a genetic mutation that impairs hearing. The news, detailed in an e-mail he sent to Nature on 17 October, is the latest in a saga that kicked off in June, when Rebrikov told Nature of his controversial intention to create gene-edited babies resistant to HIV using the popular CRISPR tool.

Rebrikov’s latest e-mail (see box) follows a September report in Russian magazine N+1 that one deaf couple had started procedures to procure eggs that would be used to create a gene-edited baby — but the eggs that Rebrikov has edited are from women without the genetic mutation that can impair hearing. He says the goal of the experiments is to better understand potentially harmful ‘off-target’ mutations, which are a known challenge of using CRISPR–Cas9 to edit embryos.

In his e-mail to Nature, Rebrikov makes clear that he does not plan to create such a baby yet — and that his previously reported plan to apply this month for permission to implant gene-edited embryos in women has been pushed back.

Instead, he says that he will soon publish the results of his egg experiments, which also involved testing CRISPR’s ability to repair the gene linked to deafness, called GJB2, in bodily cells taken from people with this mutation. People with two mutated copies of GJB2 cannot hear well without interventions, such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. Rebrikov says these results will lay the groundwork for the clinical work.

Rebrikov adds that he has permission from a local review board to do his research, but that this does not allow transfer of gene-edited eggs into the womb and subsequent pregnancy.

Apart from the deaf couple who agreed to start undergoing procedures, he is in discussion with four other couples in which both would-be parents have two mutated GJB2 genes, he says. Rebrikov says he wants to help couples such as these to have a child with unimpaired hearing.

Rebrikov also provided further information about the couple who agreed to the procedures in his most recent e-mail. In September, N+1 had reported that the couple didn’t sign a consent form and had backed away from the idea of creating a gene-edited child, citing personal reasons.

But Rebrikov now says that this is only a temporary hurdle. He notes that the woman who donated the eggs has taken a one-month ‘pause’ while she gets a cochlear implant.

Rebrikov also emphasized that he will not move forward without approval from the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. “I will definitely not transfer an edited embryo without the permission of the regulator.”

That might not come soon. Last week, the ministry released a statement saying that production of gene-edited babies is premature. Rebrikov says “it is hard to predict” when he will get permission, but it will be after all the necessary safety checks.

Doubling down

Rebrikov shot to fame in June with the news of his plans to make HIV-resistant babies. The news shocked international researchers, who feared that he was following in the footsteps of Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who announced the controversial birth of the world’s first babies, twin girls, with edited genomes last year.

Rebrikov plans to use CRISPR to disrupt the same gene that He did — CCR5. The protein made by the CCR5 gene allows HIV to enter cells, and people with a mutated copy of this gene are much less likely to get the virus. But many scientists say that the benefits — possible resistance to HIV — are not worth the unknown risks of gene editing, because there are other ways to prevent passing HIV from parent to child.

According to Rebrikov’s latest e-mail, he has not abandoned plans to edit the CCR5 gene. He says he started looking for women with HIV who wanted to have a baby and who have responded poorly to HIV drugs. He argues that such people might be good candidates for the procedure because they have an elevated chance of passing the virus to their children, although many scientists think any attempt to use gene editing in embryos to modify CCR5 is misguided. He told Nature he is still looking for such women. “But there are very few of them,” he says.

In the meantime, Rebrikov has taken on another project — repairing the GJB2 gene in human embryos.

Some scientists and ethicists also call into question the benefits of this procedure because hearing loss is not a fatal condition. “The project is recklessly opportunistic, clearly unethical and damages the credibility of a technology that is intended to help, not harm,” says Jennifer Doudna, a pioneer of the CRISPR gene-editing tool and a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

In the wake of He’s explosive revelation last November, the World Health Organization tasked a committee with developing an international framework to govern the clinical use of gene editing. In August, the WHO committee also launched an international registry of clinical research using gene editing in humans to oversee this practice. An international commission created by the US National Academy of Sciences, US National Academy of Medicine and the Royal Society of the United Kingdom is also preparing a framework to guide clinical research in germline gene editing, which is expected to be released in spring 2020. The commission will hold a public meeting on 14–15 November to gather ideas for it…