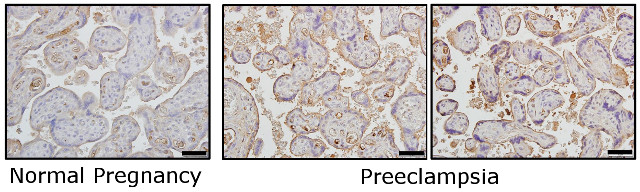

As many as 8 percent of pregnant women develop a condition known as preeclampsia, a spike in blood pressure characterized by the reduced formation of placental blood vessels. Previous research has suggested that reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play a role in triggering the untreatable condition, which causes up to 15 percent of maternal deaths and 5 percent of stillbirths 翻墙 globally. A handful of clinical trials have even attempted to reduce the risk of preeclampsia by targeting ROS accumulation, but treated women often had worse outcomes. Now, a study in mice published today (May 16) in Science Signaling provides a potential clue as to why: ROS may actually help protect against preeclampsia by increasing blood vessel generation in the placenta.

The results “were exactly opposite” of what the researchers had expected, coauthor Norio Suzuki, a molecular biologist at the Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan, told The Scientist in an email. Earlier work had shown that in preeclampsia patients, ROS pile up in their placentas. “However, data from this study indicated that ROS accumulation induces placental angiogenesis in a preeclampsia mouse model and improves maternal and fetal outcomes,” he said.

Using genetically modified mice, Suzuki and his colleagues recently discovered that the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, which induces the expression of detoxification and antioxidant enzymes, “is essential for protection of organs from damages in many types of diseases,” he explained. This led the researchers to wonder whether the system might also be involved in preeclampsia.

Sure enough, inactivating the Keap1-Nrf2 system in mice with induced preeclampsia led to higher levels of ROS, but unexpectedly, these animals had improved blood vessel formation. This resulted in reduced symptoms and risk of death for both the mouse mothers and their fetuses. Conversely, activating this pathway caused increased maternal mortality and higher rates of miscarriage.

While the molecular mechanisms by which ROS regulate placental angiogenesis remain unknown, Suzuki noted, the results suggest that oxidative stress may be important to a healthy pregnancy, and this antioxidant system may provide “plausible candidates for preeclampsia treatment in future.”

Guillermina Girardi, the chair in women’s health at King’s College London, raised concerns about the mouse model Suzuki and his colleagues used, noting that it’s unclear if the rodents have abnormal invasion of cells called trophoblasts into the maternal uterus. This invasion is thought to be the primary cause of the hypertension that characterizes preeclampsia.

Moreover, she added, the authors observed thickening of the heart’s muscle wall following the development of hypertension—something that “clearly does not happen in other mouse models of preeclampsia characterized by abnormal trophoblast invasion,” she said. Thus, “the model fails to reproduce the sequence of events that occur in women during pregnancies affected by preeclampsia.”

Suzuki acknowledges the limitations of the mouse model he and his colleagues used, and emphasizes the importance of testing the role of ROS in other mouse models of preeclampsia. “Researches using animal models always have limitations, and it is impossible to explain everything about animal models in a paper,” he said. “We are thinking that effects of ROS on improvements in preeclampsia through inducing placental angiogenesis could not be found without our mouse model.”