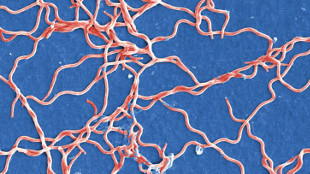

It starts with a tick bite. This may be followed by the characteristic bullseye rash. And then the other symptoms of Lyme disease appear. Fever, fatigue, body aches, and headaches can all set in.

For most patients diagnosed with Lyme disease, the symptoms fade as the infection is cleared following a course of antibiotics. But for a small subset of the population, these symptoms can continue for months or years—even when diagnostic test results suggest the bacteria that causes Lyme disease,Borrelia burgdorferi, have been wiped out. Patients who present with what epidemiologist Eugene Shapiro of Yale Medical School calls “medically unexplained symptoms” are often left to seek alternative (and sometimes dangerous) treatments with limited success.

The medical community is split on post-treatment Lyme disease and a related condition, commonly called chronic Lyme disease, largely because their associated symptoms cannot be explained by B. burgdorferi-specific antibodies or cultivable bacteria. “With a urinary tract infection or something that’s persistent, you can reculture the bacteria and prove that they’re still there,” said Monica Embers, a microbiologist at Tulane University in New Orleans. “With Borrelia,” she added, “you can’t find them and prove that they’re still there.”

Embers and a colleague last month (July 27) published a study in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, which, along with a separate paper published this May in the same journal, could help explain how some B. burgdorferi might survive antibiotic treatment. Both in vitro studies demonstrated that certain drugs kill most B. burgdorferi, but leave behind a population of persisters—bacteria that are genetically identical to their kin, but become dormant or so slow-growing that they aren’t killed by microbiostatic antibiotics. Kim Lewis, a biochemist at Northeastern University in Boston, who led the May study, noted that persisters differ from antibiotic-resistant bacteria in that they do not have special adaptations that make antibiotics ineffective, they simply survive antibiotic exposure through some other means.

Both Embers and Lewis said they were unsurprised by the presence of these hardy bacteria in increasingly dense cultures of B. burgdorferi. “All bacteria form persisters,” said Lewis. While a 2013 study indicated B. burgdorferi don’t form persisters in vitro, Lewis said the density of bacteria required for such bacteria to emerge wasn’t reached in those experiments.

The observation that B. burgdorferi can form dormant or slow-growing persisters in vitro offers a possible explanation for why scientists have generally been unable to culture the bacteria from antibiotic-treated infected animals, despite being able to transfer and recover the pathogen or its DNA through a tick bite in a process called xenodiagnosis.

“There’s a whole new interest in what are called viable but non-cultivable bacteria,” said Embers. It’s possible, she said, that at some point during infection or in response to antibiotics, B. burgdorferi morphs such that it can no longer be cultured in vitro, forcing scientists to depend on genetic evidence of its presence. This is problematic: many Lyme disease researchers contend that genetic material may be left over from terminated infections, while others—including University of California, Davis, immunologistNicole Baumgarth—argue that immune cells degrade free DNA so quickly that it’s unlikely traces of B. burgdorferi would turn up in the absence of the bacteria.

To Baumgarth’s mind, it is equally possible that post-treatment Lyme disease may result from an ongoing infection, remnants of uncleared bacteria, or an autoimmune process. “There are no studies done in humans that convincingly rule in or out any of those possibilities,” she said.

Shapiro noted that antibiotic refractory arthritis, a medically accepted diagnosis, likewise may result from an ongoing autoimmune process or slow clearance of antigen that fuels persistent inflammation in patients who have had Lyme disease.

All of these explanations, Baumgarth said, involve some immune disturbance. In PLOS Pathogens, Baumgarth’s group last month (July 2) showed that B. burgdorferi prevents long-term immunological memory in mice, and instead leads the animal’s defense system to favor short-lived antibody-producing cells that quickly die off unless there is bacteria present to maintain the response. While this is happening, Baumgarth said, B. burgdorferi may be varying its surface antigens. “When a mouse has antibodies to a certain surface proteins on Borrelia, there’s a lot of pressure to downregulate that surface antigen.”

Alterations of surface antigens and antibiotic treatment could bring an end to the antibody response to B. burgdorferi, and if persisters form in mice after antibiotic treatment, there would be no antibody from memory cells to clear them up, she continued. Much work remains to determine whether the same conditions apply to human infection; if the findings hold up in people, they could have implications for diagnostic practices, since both acute and post-treatment Lyme disease patients often have negative serology.

Embers said her group is currently performing RNA sequencing analysis on B. burgdorferi before and after antibiotic treatment to find out how the bacteria may be changing during drug administration and whether persisters can be identified apart from a dormant or slow-growing state. “It’s really important to do this work in vitro,” she said. “But what we’d like to see is a shift to looking in vivo.”

Even if persisters do appear in vivo, some scientists are not convinced that they will be clinically important. “You still have to show that there’s some disease associated with persistence,” said Shapiro. Using PCR, microscopy, or xenodiagnoses, researchers have yet to link the continued presence of B. burgdorferi to the symptoms reported by patients who are thought to have post-treatment Lyme disease.

Lewis said he plans to search for B. burgdorferi persisters in a mouse model and determine whether they can be eradicated in vivo by delivering antibiotics in pulses. To date, his group found in vitro evidence to suggest that persisters “wake up” and can become susceptible to antibiotics again when the drugs are washed away. “That, in principle, should be possible to emulate in people,” he said.