The results are in from the first monoclonal antibody drug for COVID-19 tested in humans. The small Phase 2 clinical trial involving 452 participants shows the drug can reduce the need for hospitalization in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 symptoms compared to control patients. The drug’s manufacturer, Eli Lilly, released a statement announcing the trial results, and the raw data have not yet been peer-reviewed or published.

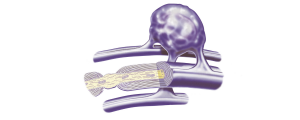

Convalescent plasma treatments, which work by giving a patient a myriad of antibodies from recovered COVID-19 patients, have received emergency use authorization from the US government, but their benefits are uncertain. Lilly’s LY-CoV555 is monoclonal and provides a singular, targeted antibody treatment that can be scaled up and provide consistent dosing. The medicine binds to the spike protein on the SARS-CoV-2 virus, preventing it from infecting cells. Other antibodies bind to the virus as well but can’t always block infection.

“These interim data from the BLAZE-1 trial suggest that LY-CoV555, an antibody specifically directed against SARS-CoV-2, has a direct antiviral effect and may reduce COVID-related hospitalizations,” Eli Lilly chief scientific officer Daniel Skovronsky says in the statement. “The results reinforce our conviction that neutralizing antibodies can help in the fight against COVID-19.”

See “First Antibody Trial Launched in COVID-19 Patients”

The company reports that out of the 302 patients given the drug, five ended up in the hospital, a total of 1.7 percent. This rate is a marked improvement over the 150 patients who received a placebo, among whom nine, or 6 percent, required a hospital stay. There were no reports of significant adverse reactions.

According to Science, most of the patients who ended up in the hospital were older or had a high body mass index—two known risk factors for COVID-19 complications.

Patients who received the drug were divided into groups by dosage and were given either 700, 2,800, or 7,000 mg of the drug. Viral load measurements compared initial samples to those on Day 11, and doctors monitored patients for health outcomes through Day 29. Ultimately, the 2,800 mg dose appeared to be the Goldilocks sweet spot and was the only one that met the goal viral load by Day 11.

“This is a good start,” Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute, who was not involved with the study, tells STAT. “A lot is pinned not only on Lilly but on the whole family of these [monoclonal antibodies], because even though they’re expensive and they’re not going to make a gajillion doses, they could make a big difference in the whole landscape of the pandemic.”

The drug was developed from an antibody harvested from a COVID-19 survivor. Carl Hansen, the CEO of AbCellera, a biotech firm collaborating with Eli Lilly on LY-CoV555, told The Scientist earlier this year that the companies went from blood sample to clinical trials in just three months. “It would normally take anywhere from two and a half years to five years for a program like this to move forward,” he said.

Studies involving other treatment arms are ongoing, with preliminary results expected by the end of the month. Moving forward, the company plans to use LY-CoV555 in a population with a higher risk of COVID-19–related complications, such as old age or obesity.