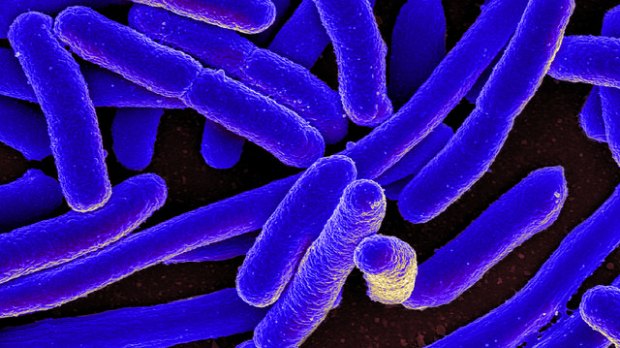

When animals eat, gut bacteria numbers spike. It also appears that the organisms have a means of limiting growth: by sending signals to their host to stop eating. Researchers reported in Cell Metabolismtoday (November 24) that E. coli produce proteins that stimulate the release of satiety hormones and curb eating in mice and rats.

“It suggests that the growth and activity of the microbiome might specifically regulate appetite and feeding behavior,” Kevin Murphy, an endocrinologist at Imperial College London who was not involved with the study, told Science News.

The researchers observed that commensal E. coli are no longer proliferating 20 minutes after an animal eats, and that the bacteria produce a different suite of proteins than during mealtimes. Giving these proteins to rodents caused the release of peptide YY, which signals fullness, and caused the animals to eat less.

“We now think bacteria physiologically participate in appetite regulation immediately after nutrient provision by multiplying and stimulating the release of satiety hormones from the gut,” study coauthor Sergueï Fetissov of the University of Rouen and INSERM in France said in a press release. “In addition, we believe gut microbiota produce proteins that can be present in the blood longer term and modulate pathways in the brain.”

Murphy said more studies are needed to determine whether the results from Fetissov are physiologically relevant.