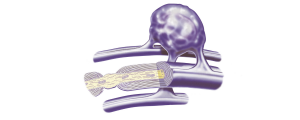

A hallmark of the disease multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory autoimmune attack1 on the proteins of the myelin sheath, a structure that wraps around the nerve fibres that project from neurons. The myelin sheath provides protection and nourishment to nerve fibres and enables efficient transmission of nerve impulses. Myelin-sheath injury causes a range of symptoms, depending on the neurons that are affected. Which immune-system cells and protein targets have key roles in the initiation and progression of multiple sclerosis is not fully understood, and such information might aid the development of new treatments. Writing in Cell, Jelcic et al.2 present an analysis of immune-system cells found in people with multiple sclerosis that deepens our understanding of how immune cells might contribute to this disease.

One factor linked3,4 to the risk of developing multiple sclerosis is the possession of a particular version of a protein called HLA. HLA proteins enable cells to display antigens — fragments of proteins — on their surfaces. If the receptor for an antigen (the T-cell receptor; TCR) on a T cell recognizes an antigen presented by an HLA protein, the T cell is activated to trigger an immune response against cells that express the antigen. Variations in the antigen-binding capacity of different HLA proteins and in the antigen-recognition capacity of TCRs enable the body to respond to a wide range of antigens associated with disease-causing microorganisms. However, there is a danger that if an HLA protein efficiently binds an antigen that is normally part of the body, and if a T cell that recognizes the HLA–antigen complex is activated, autoimmunity could develop. Such a mechanism might underlie the fact that the version of HLA called HLA-DR15 is a risk factor for multiple sclerosis3, and is estimated4 to contribute 60% of the total genetic risk for developing the condition.

T cells from people with multiple sclerosis are more prone to divide in vitro than are T cells from people without the condition3. Such cell division is reminiscent of the division that occurs as the result of normal immune-cell activation by an antigen stimulus, but in this case it does not seem to require the addition of an antigen stimulus to the sample of immune cells3. This suggests either that the normal requirement for antigen recognition is being bypassed, or that these T cells recognize an antigen that is present on other immune cells in the blood sample. Jelcic et al. investigated further, analysing in more detail the behaviour of immune cells in blood samples of people with multiple sclerosis. They convincingly demonstrate that both T cells and another type of immune cell called a B cell from these samples could proliferate when grown in vitro. The authors term this type of division autoproliferation, because it occurs spontaneously in vitro without the addition of an antigen.

Jelcic et al. found that signalling through a TCR-initiated T-cell proliferation, and that cell proliferation was associated with the production by T cells of a signalling protein called IFN-γ (Fig. 1), which is associated with multiple sclerosis5. IFN-γ is a potent activator of a category of immune cells called macrophages, which directly damage the myelin sheath6,7 in multiple sclerosis….