In a new study, researchers compared genetic mutations in patient tumours to those in cancer cell lines and then tested the cell lines’ responses to therapeutic compounds. By analysing where these datasets overlap, researchers can begin to predict on a large scale which drugs will best fight various cancers.

When developing new anti-cancer drugs, researchers often rely first on cancer cell lines in the lab. “You can’t screen hundreds of drugs across a single patient. It’s not possible,” says Ultan McDermott, a cancer clinician and researcher at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. “But you can do that with cell lines – you can expose them to many different drugs and ask questions about which is more or less sensitive.”

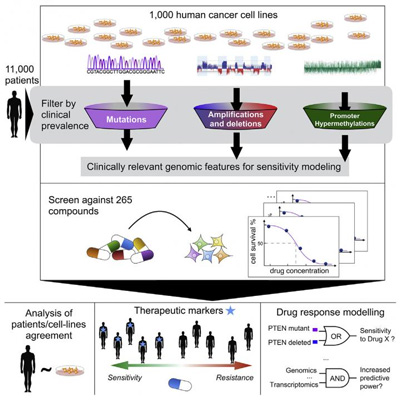

How closely these cell lines match what actually happens in a human tumour has been unclear, however, and previous efforts to model drug response using cancer cell lines were done on a relatively small scale. To investigate further, McDermott, Mathew Garnett, a cancer biologist at the Sanger Institute, and their colleagues analysed data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and the International Cancer Genome Consortium, and other studies, gathering genetic information for more than 11,000 tumour samples.

The team then compared these tumour samples to about 1,000 cancer cell lines used in labs, looking for lines that had the same types of mutations as the patient samples – and therefore might more closely mimic patient responses.

A step closer to identifying drug interactions

Next, the researchers looked for the genetic mutations that could best predict the cancer cells’ response to 265 different anti-cancer compounds. The drugs covered a range of mechanisms, including chemotherapeutics, small-molecule inhibitors, epigenetic modulators, and cell death regulators.

Many of the mutations that occurred both in tumour samples and cell lines did signal whether the cancer cells would be sensitive or resistant to different compounds, largely depending on the type of tissue the cancer originated in. “If you can identify the clinically relevant features in cell lines and correlate those with drug response, you’re one step closer to identifying a drug interaction that could be important for a patient,” says McDermott.

Going forward, the researchers are creating a web portal to share their data, which will allow cancer researchers to see which cell lines most closely mirror the patient condition they aim to emulate and how those cell lines respond to different drugs.