Multicellular life requires individual cells to cooperate in a way that benefits the organism. Cells that are uncooperative because they are damaged or dysfunctional, and that pose a threat, are either eliminated by cell death or undergo a usually irreversible growth arrest called senescence1. Senescent cells typically never divide (although there are some rare examples of cells exiting senescence and resuming division), but they can persist in tissues and contribute to ageing and cancer progression2,3. Writing in the Journal of Cell Biology, Tonnessen-Murray et al.4 reveal a deadly activity that underlies the persistence of senescent cells — they can eat their neighbours alive.

Cellular entry into senescence benefits an organism because it inhibits cancer development by preventing the division of cells that have accumulated extensive DNA damage or that express cancer-promoting genes called oncogenes2,5. Senescent cells are metabolically active6, and this is characterized by their secretion of proinflammatory molecules as part of a phenomenon termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) response2. Senescent cells can promote cancer progression and resistance to anticancer therapy in some contexts, as a result of the secretion, through SASP, of growth factors and immune-signalling molecules called cytokines2.

Chemotherapy that damages the DNA of cancer cells can result in their death or their entry into senescence. Tonnessen-Murray and colleagues investigated the effects of chemotherapy-driven senescence in breast cancer cells in mice treated with the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin. Under the microscope, they saw senescent cells eating and digesting entire neighbouring cells (Fig. 1). This striking observation was made in breast tumours formed of mixtures of transplanted cancer cells, which were engineered to express red or green fluorescent proteins. It can be difficult to observe a cell being internalized by another cell (a process termed engulfment) in cancer tissues. By growing tumours with mixtures of fluorescently labelled cells, the authors could clearly identify red- or green-labelled cells being taken up into neighbouring cells labelled by the other colour.

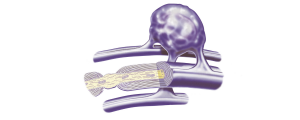

Figure 1 | Cellular cannibalism. Chemotherapy drugs can cause cancer cells to enter a state of senescence, which is usually associated with an irreversible halt to cell division. However, these cells can promote tumour survival by secreting growth factors and signalling molecules called cytokines in a process termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) response2. Tonnessen-Murray et al.4 report studies of breast cancer in mice which reveal that this type of senescent cell takes up (engulfs) and digests neighbouring living cells. The cells are engulfed by a process that has molecular characteristics of phagocytosis, an engulfment process that immune cells use. Once ingested, the cells are enveloped in membrane from an organelle called the lysosome and digested. This might account for a portion of the numerous lysosomes that are a hallmark of senescent cells. This degradation provides metabolic building blocks for the cell. Senescent cells that have ingested their neighbours survive for longer than senescent cells that have not.

Engulfment also occurred at high rates for mouse and human breast cancer cells grown in vitro and treated with doxorubicin or another chemotherapeutic drug, paclitaxel. Ingestion peaked at 4–6 days after drug treatment, a time that correlated with the induction of senescence. The cells that were engulfed by the senescent cells were neighbouring senescent or non-senescent cancer cells. They showed no sign of being dead, and engulfment occurred even in the presence of a cell-death inhibitor molecule. This led the authors to conclude that the ingested cells were being eaten alive.

Ingested cells are broken down in a digestive organelle called the lysosome. Crucially, senescent cells that ate their neighbours survived longer in vitro than those that did not. This finding suggests that metabolic building blocks retrieved from the lysosomal digestion of neighbouring cells were being used by senescent cells to promote their survival…