Zika is a mosquito-borne, sexually transmissible virus that is now known to cause a variety of birth defects. The ongoing epidemic of Zika virus infection in parts of the Americas is unlike any outbreak public health officials have handled to date. Thankfully, scientists around the world heeded the call for more basic research to better understand this mysterious pathogen.

Here’s a look back at 12 months of Zika news.

Travel warnings

Experts had been tracking the emergence of Zika virus in Brazil since 2014. This January, “out of an abundance of caution,” the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued its first travel warning. At the time, the agency recommended that pregnant women not travel to areas in which the virus was actively circulating. In the months since, the CDC has issued scads of similar travel warnings, which now cover more than 50 countries—and include parts of the U.S.

Diagnostic troubles

Zika virus infection is often asymptomatic. As researchers began linking birth defects—including microcephaly—and other abnormalities to Zika, one immediate focus was developing better diagnostics. By February, several tests meant to complement existing PCR tests—which can be used to detect the virus in a person’s blood—were already in the works. More sensitive and specific diagnostics were sorely needed, however, because “by the time [patients] make it into the clinic, the virus is likely gone or it’s at the tail end, beyond the limit of detection,” Nikos Vasilakis, who was then developing Zika tests at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, told The Scientist at the time.

Epidemiological estimates

Meantime, epidemiology experts began plotting the spread of Zika. In early March, researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research released an analysis of Zika’s northward spread, based on projected international travel, socioeconomic data, and weather patterns favored by the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that transmit the virus. The CDC took this estimate into account, but cautioned that Zika could reach even farther north. In an April eLife study, scientists used similar techniques to map out the worldwide risk of Zika, estimating that some 2.17 billion people may be in the virus’s path.

Basic research

Reports of links between Zika and various diseases trickled in throughout 2016. Although the CDC did not declare a causal link between in utero Zika virus infection and microcephaly until April, the World Health Organization (WHO) in February said it was highly likely that Zika causes the birth defect, based partly on a The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) study in which scientists reported finding a complete Zika genome in the brain of an aborted fetus that had microcephaly.

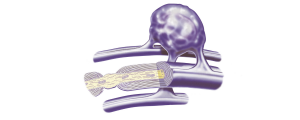

By March, researchers presented in Science the first detailed look at the pathogen’s structure. “Now that we have the structure, there is a lot of work that we can start directed towards developing [prophylactic] vaccines and antiviral compounds and antibodies,” coauthor Michael Rossmann of Purdue University told The Scientist at the time. (Scientists continued to progress toward a Zika vaccine throughout 2016, culminating in a series of promising results in macaques.)

Also in March, researchers proposed a biological mechanism for how Zika infection could cause microcephaly. The team’s results were published in Cell. “The study demonstrates that human neuron-like cells can be infected with Zika virus and that infection leads to death and reduced growth of the infected cells,” Andrew Pekosz of Johns Hopkins University, who was not involved in the study, told The Scientist at the time. “This is important because this may be a way to study the damage induced directly by infection.” (Animal studies—first in mice, then in monkeys—later supported these findings.)

That same month, a landmark study published in NEJM found that more than 25 percent of women taking part in a study of Zika virus infection during pregnancy had fetuses with potentially serious abnormalities. Between February and April, scientists reported a link between Zika virus infection and Guillain-Barré syndrome, a disorder similar to multiple sclerosis, and hearing and vision problems. Late last month, researchers reported that even fetuses that don’t show signs of in-utero infection can develop Zika-associated brain abnormalities after birth.

Eradication efforts

Other scientists have turned their attention toward eradicating Zika. After a May 4 study found that Wolbachia bacteria can block Zika’s spread, researchers began planning to release millions of mosquitoes infected with the bacteria, in an attempt to dampen the abilities of these mosquitoes to transmit the virus. As of October, the approach was slated for testing in Brazil and Colombia over the course of two years. In a separate attempt to weaponize insect vectors against Zika, Florida voted to release a swarm of male mosquitoes engineered to produce offspring who die before reproducing. The notion of genetically modified mosquitoes proved contentious, however.

Looking ahead

Scientists have predicted that ongoing Zika virus outbreaks are now likely petering out. In a paper published in Science in July, researchers noted that the epidemic was peaking and proposed that it could end entirely within three years, with numbers of cases dropping substantially by the end of 2017. In November, WHO said Zika was no longer a public health emergency of international concern, a move critics deemed premature.

Late last month (November 28), Texas became the second U.S. state to report local transmission of Zika via mosquito bite. (Florida saw its first such case in July.) “We knew it was only a matter of time before we saw a Zika case spread by a mosquito in Texas,” John Hellerstedt, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said in a statement. Last week (December 14), the CDC said Texas had reported a total of five cases thought to have been acquired by local mosquito bites.

The agency instated a travel guidance for Brownsville, Texas. Its existing travel guidance for Florida’s Miami-Dade County remains in effect.